By now, many people are aware that Ishtar has nothing to do with Easter. However, there are still a number of Bible teachers, such as Chick.com and LastTrumpetMinistries who preach that Easter is derived from the cult of Ishtar. Is there a reason for this myth? What about the Easter symbols, like bunnies and eggs? Weren’t they associated with Ishtar? Below I will be examine the vast majority of extant texts related to Ishtar and variant goddesses, such as Inanna, Ashtoreth, Astarte, etc.

Was Easter Named After Ishtar?

People without a solid foundation in history and culture have been duped into believing that Easter is a celebration that is about the goddess Ishtar. It’s easy to see why this is believable. Ishtar is the patron goddess of some of the dominant cultures mentioned the Old Testament, and Easter sounds a lot like Ishtar. Most people who have done even a cursory study of the Babylonian culture already know that they held Ishtar in high status among the gods. They had temples created for her. They had stories and poems about her. She even gets a role in the famous tale of Gilgamesh and the Great Flood (2000 BCE). Her name also appears on many monuments in the Ancient Near East, such as the Banquet Stela of Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BCE). She was widely written about in the culture. A large collection of writings that speak of Ishtar can be found below. One should notice that they are quite ancient and date back long before Jesus ever stepped foot in Judea. In fact, the Babylonian Empire was long gone by the time the Roman Empire formed. It’s connection to anything relating to early Christianity seems to be purely mythical. One will also notice that the many stories of Ishtar paint a picture of her that seems to be completely unrelated to anything having to do with Easter or its customs.

Where did all this confusion about Ishtar even begin?

In 1853 Alexander Hislop published a book titled “The Two Babylons“, attempting to conflate the Roman Catholic church with the famous whore of Babylon. The book was filled with what modern people would call conspiracy theories and badly researched history. He condemns many of the church’s practices as being pagan and the church of essentially being a surrogate of the Devil. Today, Hislop’s theories have mostly died off. However, a few groups have tried to revive portions of this book. David Icke, the guy behind the lizard people conspiracy has latched onto material from this book, as well as flat earthers and KJVO advocates. Needless to say, it will likely remain fodder for conspiracy theorists for generations still to come.

Ancient Texts

There are lot of ways to gather information about Ishtar. Many books have been written about her. However, I always feel that the best way to do research is the slow way….. go find the primary sources and read them. In this article I read as many ancient texts that contained mentions of Ishtar as I could find. However, some were removed from the list because they had nothing of value to add to understanding who Ishtar was. For all the other texts I have provided whatever information about Ishtar was learned from that text.

The list of Ishtar texts below are listed in no particular order but they are accompanied by approximate text dates and the resource in which the story can be found. The texts are listed by date, location, and source. The sources, however, are abbreviated to save space.

The abbreviation ANET stands for Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, by James Pritchard. The COS abbreviation is referring to the 3 volume (now 4 volumes, 2019) set known as The Context of Scripture, by William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger. The abbreviation AT stands for Alalakh Tablets. At this point in history I am not aware of the various ways to obtain the Alalakh Tablets other than from the library. The abbreviate ETCSL stands for Electronic Text Corpus of the Sumerian Language.

Sumerian Texts Concerning Inanna (Ishtar)

- Inanna’s Descent to the Underworld [c. 2000 BCE] (ANET 52)

- An ancient Sumerian epic which features the older name for Ishtar (Inanna). Texts featuring Inanna are usually older than the ones featuring Ishtar.

- There are a number of ancient symbols associated with Inanna that come from this story. They are described early in the story because they are needed for her descent into the netherworld. They are listed below and one can see that none of the symbols appear to have any relationship with any Easter celebration.

- (Crown) The šugurra, the crown of the plain, she put upon her head,

- (Wig) The wig of her forehead she took,

- (Measuring line) The measuring rod (and) line of lapis lazuli she gripped in her hand,

- (Necklace) Small lapis lazuli stones she tied about her neck,

- (precious stones) Sparkling … stones she fastened to her breast,

- (A ring) A gold ring she put about her hand,

- (Breastplate) A breastplate which …, she tightened about her breast,

- The storyline of this text is about Inanna descending into the underworld, being made captive as a dead person, and then being revived by the water of life and rising from the dead. This dying and rising mythology was connected to the ancient season cycle, similar to the Ba’al cycle in northern Canaan and Assyria.

- Dumuzi and Enkimdu: The Dispute between the Shepherd and the Farmer [c. 2000-1700 BCE] (ANET 41)

- This short story describes a shepherd and a farmer verbally competing for Inanna’s hand in marriage. We learn nothing substantial about Inanna from this narrative other than the fact that she has a brother name Utu and that he wanted her to marry a shepherd named Damuzi.

- The ending of the text is damaged so it is unclear who she chose but we know from many other texts that she chooses Damuzi. Thus, her connection to Dumuzi begins here and goes on for centuries.

- The Deluge [c. 2900 BCE] (ANET 42-44)

- Inanna is merely a bystander in this epic. The Sumerian deities decide to flood the earth just like in the Noah story. Inanna cries and is terrified when the world is flooded.

- Gilgamesh and Agga [c. 2000-1500 BCE] (ANET 45-47)

- Inanna is only mentioned in passing. It is said that the famous Gilgamesh performed mighty deeds for Inanna.

- In other ANE texts Gilgamesh rebukes a marriage proposal from Inanna. The Gilgamesh and Agga story assumes the reader knows something about Gilgamesh and Inanna already.

- Statue of King Kurigalzu Inscription [c. 1375 BCE] (ANET 57-59)

- This fragmented inscription mentions Inanna a few times as well as a dwelling created for her. In it we discover another nickname for Inanna, Belitili.

- “… they gave to Inanna … as a share; they built for Belitili the …, the large grove, her abode of lordship“

- The final fragment of this artifact is too broken to discern but it appears to be a small list of duties assigned to Inanna. Just one duty can be read.

- “to raise high the position of those who turn evil to good, they gave to Inanna … among her portions”

- This fragmented inscription mentions Inanna a few times as well as a dwelling created for her. In it we discover another nickname for Inanna, Belitili.

- Self-Laudatory Hymn of Inanna and Her Omnipotence [Tablet dating unknown] (ANET 578)

- Enlil, the head of the pantheon, exalts Inanna to a place above the other gods in the pantheon and lets her into his palace. The hymn is written from the voice of Inanna after being exalted by Enlil. Her titles and duties are listed below.

- Queen of heaven and life-giving wild cow of Enlil.

- Lord of the battle and lord of the flood.

- A scepter is placed in her hand.

- She is draped in a royal garment.

- Enlil, the head of the pantheon, exalts Inanna to a place above the other gods in the pantheon and lets her into his palace. The hymn is written from the voice of Inanna after being exalted by Enlil. Her titles and duties are listed below.

- Hymnal Prayer of Enheduanna: The Adoration of Inanna in Ur [c. 2200 BCE] (ANET 579/COS 1.160)

- This hymn is purported to have been uttered by the daughter of Sargon the Great, Enheduanna. Of the many ancient texts, few offer more descriptions of Inanna than this one. Her many descriptions are listed below.

- Queen of the radiant light and the ordinances (think of an ordinance like a heavenly law of physics) sometimes combine with an object.

- Life-giving woman with extensive bejeweling (she’s covered in jewels)

- Owner of the 7 ordinances (also seen in Inanna’s descent into the underworld)

- These ordinances are described as being tied around her hand and against her breast.

- She is said to have filled the land with venom, fire, and floods from the mountains

- She is called a rider of beasts, which should be a familiar image since she is often seen riding or conquering a lion.

- Maker of the storms.

- Defeater of the foreign lands.

- She is described as joyful but with an anger that cannot be soothed.

- Wild-cow (see notes on the Self-Laudatory Hymn of Inanna).

- Beloved of Damuzi.

- Queen of the horizon and the zenith.

- In one section of the hymn Inanna is praised with a list things she is known for….

- You are known by your heaven-like height,

- You are known by your earth-like breadth,

- You are known by your destruction of rebel-lands,

- You are known by your massacring (their people),

- You are known by your devouring (their) dead like a dog,

- You are known by your fierce countenance.

- You are known by the raising of your fierce countenance,

- You are known by your flashing eyes.

- You are known by your contentiousness and disobedience,

- You are known by your many triumphs.

- This hymn is purported to have been uttered by the daughter of Sargon the Great, Enheduanna. Of the many ancient texts, few offer more descriptions of Inanna than this one. Her many descriptions are listed below.

- Dumuzi and Inanna: Pride of Pedigree [c. 2100-1800 BCE] (ANET 637)

- This ancient Sumerian poem describes a lover’s debate about who’s family line is the greatest, which is settled by the pair making love. Both Inanna and Dumuzi are proud of their differing heritage.

- In this poem we only learn one thing significant to the discussion which is that Inanna is described as a temple prostitute. Her connection with prostitution is well documented in her patron city of Uruk.

- Dumuzi and Inanna: Love in the Gipar [c. 2100-1800 BCE] (ANET 638)

- This love poem describes a number of gifts that are given to Inanna. In it she chooses some of her most favorite and typical gems and jewelry. Certain pieces of jewelry like lapis lazuli necklaces are common among Inanna mythology. She also selects a number of items related to love making. This poem is also usually seen as a pre-consumation setting.

- She picks the buttocks-stones, puts them on her buttocks,

- Inanna picks the head-stones, puts them on her head,

- She picks the duru-lapis lazuli stones, puts them on her nape,

- She picks ribbons1 of gold, puts them in her hair of the head,

- She picks the narrow gold earrings, puts them on her ears,

- She picks the bronze eardrops, puts them on her ear-lobes,

- She picks “that which drips honey,” puts it on her face,

- She picks “that which covers the princely house,” puts it on her nose,

- She picks “the house which …,” puts it on her …,

- She picks cypress (and) boxwood, the lovely wood, puts them on her navel,

- She picks a sweet “honey well,” puts it about her loins,

- She picks bright alabaster, puts it on her anus,

- She picks black … willow, puts it on her vulva,

- She picks ornate sandals, puts them on her feet.

- After preparing herself for the wedding, Inanna sends a messenger ahead to prepare the house for her and her new lover.

- This love poem describes a number of gifts that are given to Inanna. In it she chooses some of her most favorite and typical gems and jewelry. Certain pieces of jewelry like lapis lazuli necklaces are common among Inanna mythology. She also selects a number of items related to love making. This poem is also usually seen as a pre-consumation setting.

- Dumuzi and Inanna: Courting, Marriage, and Honeymoon [c. 2100-1800 BCE] (ANET 639)

- Again Inanna is referred to as a hierodule (temple servant/prostitute). Inanna was commonly seen as a priestess or servant of a scared temple.

- Not much is learned from this poem about Inanna except that she accepts the marriage proposal of Damuzi and she is seen again preparing herself with a necklace of lapis-lazuli.

- Dumuzi and Inanna: The Ecstasy of Love (Also known as “Love by the Light of the Moon”) [c. 2100-1800 BCE] (ANET 639-640/COS 1.169C)

- This short poem teaches us a few more things about Inanna and Damuzi. We also learn that Inanna’s mother is named Ningal, however, her parents tend to change over time. Most of the ANE deities have multiple origin stories and multiple parents. This is because the myths are very old and got changed to adapt to new cultures.

- The premise of this poem is Inanna being seduced by Damuzi but much of the story to lost to history, as the tablet is broken. The reverse side of the tablet implies that Damuzi companies her to her mother’s house in order to propose marriage to Inanna’s mother, Ningal and her father, Sin.

- Inanna and the King: Blessing on the Wedding Night [c. 2100-1800 BCE] (ANET 640)

- This love poem is not between Inanna and Damuzi but is a blessing from a king on Inanna. He has prepared a temple for her to come to and consummate her wedding night in. Nothing is learned about Inanna in this letter, however, the bed is described to contain lapis, a common stone associated with the goddess.

- Dumuzi and Inanna: Prayer for Water and Bread [c. 2100-1800 BCE] (ANET 641)

- This collection of tablets has 4 sections. The first 2 sections are monologs by Inanna. It ends with a king praying to the goddess for fertility and blessings.

- Inanna’s first monolog describes her bringing home animals and plants from the abzu. The abzu was the life-giving waters that was below the earth. What she brings back from the abzu is listed below.

- Dog

- Lion

- Boxwood

- Halub wood

- The story then shifts to Inanna describing her journey to the temple of Enlil. While there she seemingly chastises other deities but it is not clear why due to missing pieces. But Inanna’s temper is often included in Mesopotamian myths.

- Inanna is again pictured as a deity of both love and war.

- Dumuzi and Inanna: Prosperity in the Palace [c. 2100-1800 BCE] (ANET 642)

- This is an erotic love poem in the form of a monolog of Inanna. In she she describes her sexual desires and a few other things. She likens her vagina to a garden and invites Damuzi to plow it. Naturally he responds in kind. The only thing we really learn about Inanna here is that her temple is filled will lapis lazuli, a stone that Inanna is often associated with.

- Inanna and Enki [c. 2100 BCE] (COS 1.161)

- This is a poem that tells the story of Inanna and her acquiring the divine ordinances from Enki. It is also a very sexual driven poem, praising various parts of Inanna’s sexuality. It is implied that she will gain the ordinances by tricking Enki, not seducing him. He is her father in this narrative.

- The divine ordinances are often referred to as the 7 ordinances. However, there are other ordinances that were given to mankind by the gods and there are close to 100 of them. It’s these 94 ordinances that she gains upon tricking her father in a drinking contest. These 94 ordinances range from special knowledge to magic dresses. It’s a wide sweeping list.

- When she returns to the land of mankind she distributes the ordinances to the people as she sees fit. The old men get prudence, the old women get wise-counsel, the young men get strength, so on and so forth. The location in which she distributes the ordinances is called a quay which is similar to a boat dock. This dock is named after Inanna because of her great deeds and is called the lapis lazuli quay.

- Dumuzi-Inanna: The Woman’s Oath [c. 2100-1800 BCE] (COS 1.169A)

- This is a love poem similar to the Song of Solomon in the Bible. We don’t get much information about Inanna from this poem except a description of her that is seem in some ancient icons of her.

- “Alabaster figurine, adorned with the lapis lazuli diadem, sweet is your allure!“

- This is a love poem similar to the Song of Solomon in the Bible. We don’t get much information about Inanna from this poem except a description of her that is seem in some ancient icons of her.

- Song of the Hoe [c. 2000-1600 BCE] (COS 1.157)

- This text is widely known as satyrical. It appears to be a scribal exercise that likely never saw the public. However, in the writing a few things are learned even if the text itself was not meant to be informative.

- We learn that one of Inanna’s temples was located in Zabalam. She is also referred to as a cow again. This is a common symbol for her but does not appear in her art as much as one might think.

- The Eridu Genesis [c. 1600 BCE] (COS 1.158)

- The Eridu Genesis is a wildly famous mythical account. It is often referenced as a parallel to the biblical Genesis. It contains creation, a flood, and early rulers of humanity.

- Inanna is not a major player in this epic. However, she is pictured as having pity for mankind who is about to be swept away in the flood.

- Enmerkar and the Lord Aratta [c. 2100 BCE] (COS 1.170)

- In this poem to Inanna not much is learned except that were temple is filled with lapis lazuli.

- Gilgamesh and Akka [c. 2100-1800 BCE] (COS 1.171)

- Inanna mentioned in passing as a goddess of battle.

- The Sacred Marriage of Iddin-Dagan and Inanna [c. 1900] (COS 1.173)

- This poem is interesting because it pictures the marriage rituals of Inanna and Iddin-Dagon. Typically, Inanna is pictured marrying Damuzi but Inanna has multiple lovers across time.

- In the text she is described as having a crown of horns.

- She is also associated with the brightest nighttime star. In art she is often seen next to her star.

- She is again called heaven’s wild bull, a common description.

- Inanna is also seen as taking the throne over the heavenly counsel from her patron city. She makes judgement in her counsel every new moon. Moons are also seen with Inanna in artwork.

- Later in the poem Inanna is referred to as the evening star.

- Even further into the poem she is called the day star and the morning star.

- Samsu-Ilun [c. 1700 BCE] (COS 2.108)

- This short inscription mentions Inanna by giving her credit for a military victory.

- The King of the Road: A Self-Laudatory Shulgi Hymn [c. 2000 BCE] (ANET 584-586)

- This is a hymn written about king Shulgi in first person. The hymn is not directed towards Inanna but it does mention her.

- In the hymn he claims that he is worthy of Inanna’s vulva. It sounds explicit but Inanna’s vulva is often mentioned in ancient literature. It was seen as a flower and symbol of feminine beauty.

- King Shulgi also refers to himself as the husband of Inanna and claims that she is the vulva of heaven. It was often claimed in Mesopotamia that certain kings married Inanna and some writings exist that depict what these kings did with Inanna in the bedroom.

- Curse of the Agade [c. 2000 BCE] (ANET 646-651)

- The curse of Agada is a long historiography. In it, a Sumerian theologian attempts to claim some of the military failures of Sumer as heavenly events. Essentially, the rise of the Akkadian empire has been problematic for the Sumerians and this tale explains why the Sumerians have been allowed to be trampled by other peoples. This blaming of the deities for military failures is common in ancient literature and even the Old Testament.

- The beginning of the curse of Agade starts when a foreign gift is brought to Inanna’s temple but is rejected by her. She is then said to have left the temple and waged war against the city.

- Nothing more about Inanna is really said as this piece is not necessarily about her but the curse on Agade.

- Inana and Shu-kale-tuda [c. 2300 – 1900 BCE] (ETCSL)

- In this ancient tale, Inanna is essential raped in her sleep by a human. Before the rape she is seen wearing her familiar girdle containing the seven divine powers or ordinances.

- When she wakes and realizes she was taken advantage of she inflicts plagues on the land until the culprit is found. The first plague caused all the water to turn to blood.

- The young man who raped Inanna goes into the city for hiding and Inanna casts two more plagues. The first of storms and the second of dust storms.

- The next thing Inanna did is hard to know because it’s fragmented but she appears to block the roadways from travel.

- Inanna eventually goes to her father Enki to make sure the violator will be punished and in order to find him she stretches her body like a rainbow over the mountain region and finally spots her rapist.

- Once found she verbally assaults him and decrees his fate of death and the eternal condemnation of his name.

- Enki and the World Order [c. pre-2000 BCE] (ETCSL)

- This narrative describes some of the seven divine ordinances before Inanna obtained them. In this story Inanna complains that her sisters all have been given ordinances but she has not been given a function yet. In the end, her father, Enki, describes what she was gifted with rather than a divine ordinance and then the text becomes fragmented. She seems to be gifted something but it is hard to tell what.

- The ordinances that her sisters posses are as follows:

- Nintud – the bricks and tools of a midwife

- Nininsina – The cuba stones for jewelry and is given as a wife to An

- Ninmug – A golding chisel and other tools for metal working

- Nisabu – The lapis-luzali measuring tape for making nations and boundaries. This tool later becomes one of Inanna’s main symbols.

- Nance – The holy pelican who selects and inspects the finest fish to live in the seas.

- Inana and Ebiḫ [c. 2200 – 1800 BCE] (ETCSL)

- This text starts as a hymn of praise and then transitions to Inanna speaking of herself in 1st person. She is, again, pictured as a goddess of war and as a roaring lion and wild bull.

- The narration from Inanna’s point of view describes a city from the mountains, Ehib (near Aratta), who refused to recognize her authority in heaven and earth. For this she attacks and destroys them.

- Dumuzid and Gestin-ana [c. pre 2000 BCE] (ETCSL)

- This myth tablet is about Dumuzid escaping the netherworld after he is taken there as a substitute for Inanna. However, the beginning of the text describes some of the items that Inanna is typically pictured with.

- A holy garment

- A dress of ladyship

- An ornamental head dress

- Some form of footwear but the text is broken. She was known to have sandals made from lapis-lazuli though.

Babylonian/Akkadian – Ishtar

- Sumero-Akkadian Hymn to Ishtar [c. 700 BCE] (ANET 383)

- This hymn contains a number of descriptions pertaining to Ishtar and her mythology.

- She is the greatest of the Igigi

- A mistress to the people

- She is clothed in pleasure, love, vitality, charm, and voluptuousness.

- She is described as a mother-goddess to the people

- She is also described as the queen of heaven, sharing a throne room with the king

- Prayer of Lamentation to Ishtar [c. 1600 BCE] (ANET 383)

- Like the Hymn to Ishtar, the lament repeats the descriptions of Ishtar as the queen of heaven.

- In addition, she is credited as the goddess of weapons and war.

- Ishtar is also seen providing over the divine counsel.

- As with many other descriptions of Ishtar, she is a goddess of light and brilliance.

- She wears a crown of dominion.

- Ishtar is also described as a fierce lion and a wild ox, both of which are symbols that stay closely associated to Ishtar.

- Nabonidus Basalt Stela [c. 555-539 BCE] (ANET 308)

- Ishtar is depicted as riding a chariot drawn by 7 lions. However, not much more is mentioned about her.

- The Descent of Ishtar to the Underworld [c. 1500-1200 BCE] (COS 1.108)

- This popular myth/epic, is a later Akkadian version of a Sumerian epic that is referred to as “The Descent of Inanna to the Underworld”. This later Akkadian version was the best known version to those who lived at the time the Old Testament was written. It’s ending is a bit different than the Sumerian version. In the Sumerian version when Inanna arises from the underworld she is accompanied by demons who need another victim to exchange for Inanna. She ends up sending her love Damuzi because when she entered his palace he was not mourning for her loss, as all of her family and friends were.

- In the process of entering the gates to the netherworld (as with Inanna’s story) she has to remove her outer ware. She loses the following items that she took down.

- Crown

- Earrings

- Necklace

- Toggle pins on her breast

- A girdle of birth stones around her waist

- The bangles from her wrists and ankles

- In the end Ishtar is saved by a trickster sent to get her released. However, the release of Ishtar results in the underworld demanding the life of her lover, Damuzi.

- Ritual and Prayer to Ishtar of Nineveh [c. 2350 to 2150 B.C] (COS 1.65)

- This is a prayer invoking Ishtar to come Hatti after a plague has caused some kind of damage. The prayer is then followed by a ritual of food sacrifices and libations. This ritual was likely generic but paints a good picture of what a temple ritual would have been like.

- The food and drink offered to Ishtar is bread, oats, oil cake, grain meal, a bird, oil, and wine.

- There is also an instrument dedicated to her specifically but it is not described.

- Abbael’s Gift of Alalakh [c. 2000 BC to ] (AT 1) (COS 2.127)

- This is a unique text the speaks of the city of Alalakh being given as a gift for help lent in a battle. The gifting is not of any importance for the current study but the text does mention the spear of Ishtar. This spear is probably figurative but it was not uncommon in the ancient world to keep some artifact in the temple or royal court that is said to have been owned or used by a deity, or even a legendary figure.

- For the purpose of this study it should he noted that Ishtar is not often pictured with a spear. She is pictured with a number of other weapons, however.

- Dialogue Between Assurbanipal and Nabu [c. 668 BC to 627 BC] (COS 1.145)

- This dialog is mythical in nature. It is between King Ashurbanipal of Assyria and Nabu, who was an ancient god of wisdom. In the dialog, the king is said to have been suckled by the 4 teens is Ishtar. Needless to say, it’s only figurative and Ishtar (as far as I can find) is never pictured with 4 teets.

- The Birth Legend of Sargon of Akkad [c. 2000 BCE] (COS 1.133)

- The only mention of Ishtar in this legend is by the lips of Sargon in the 1st person. She is said to have loved Sargon when he worked in the orchard. Ishtar’s association with certain trees is well attested too. Most notably, a huluppu tree.

- Diurnal Prayers of Diviners [c. pre 2000 BCE] (COS 1.116)

- The object of this diviner’s prayer is Shamash. However, Ishtar is also invoked as the goddess of battle. The associate of Ishtar with battle is a familiar one.

- Nabopolassar’s Restoration of Imgur-Enlil, the Inner Defensive Wall of Babylon [c. 658 – 605 BCE] (COS 2.121)

- This is a 1st person narration of Nabopolassar’s rise to power and restoration of the Babylonian rule. He mentions Ishtar as “the great lady” but nothing further is said of her. This likely alludes to her role as the queen of heaven.

- The London Medical Papyrus [c. 1300 BCE) (COS 1.101)

- This text is a medical procedure but modern people would consider it an incantation. It is essential a prayer for healing. Much of the text is destroyed but Ishtar is called upon during the incantation. Some have said that she has been associated with healing but little evidence for this exists.

- The Adad-Guppi Autobiography [c. 648-544 BCE] (COS 1.147)

- This is an autobiography which mentions Ishtar as a savior, likely referring to a military capacity.

- The Deir ʿAlla Plaster Inscriptions (Balaam Son of Beor Inscription) [c. 880 – 770 BCE] (COS 2.27)

- This unique inscription from Moab that is purported to be a prophecy of the biblical Balaam. Balaam was a real prophet that was known outside the Bible. In the prophecy he speaks to darkness coming over Moab and mentions a few deities who would inflict plagues and curses on the land. Ishtar is among the deities but nothing about her can be gleaned from the text other than the fact that she was among the divine council.

- Myth of Etana [c. 2334 – 2279 BCE] (COS 1.131)

- The myth of Etana depicts Ishtar as a goddess who dwells alongside the deity Shamash and can grant offspring to humans. She is a fertility goddess essentially.

- Erra and Ishum [c. 8th century BCE] (COS 1.113)

- Ishtar is not mentioned in a significant way except that her patron city, Uruk, is filled with temple prostitutes and call girls. This presence of such prostitution is likely a result of the massive fertility cult dedicated to her.

- The Autobiography of Idrimi [c. 1500 BCE] (COS 1.148)

- This inscription if autobiographical and mentions Ishtar as the patron deity of King Idrimi’s city of Alalakh.

- The Inscription of King Mesha (the Moabite Stone) [c. 840 BCE] (COS 2.23)

- The Mesha Stele refers only indirectly to Ishtar. The inscription contains a mention of a deity named Ashtar Kemosh, which was a male counterpart to Ishtar. It was a combination of Kemosh and Ishtar.

- The Weidner Chronicle [c. 1794-1816 BCE] (COS 1.138)

- Ishtar only mentioned in passing as the consort of Anu and the mother of a great son.

- The Laws of Hammurabi [c. 1792-1750 BCE] (COS 2.131)

- The very end to Hammurabi’s prolog mentioned Ishtar and her temple Nineveh. There is a brief mention that some rites are proclaimed for the goddess but nothing more.

Egyptian & Canaanite Astarte

When Egypt co-opted Ishtar she became a deity known as Astarte. She was also adopted much later by the Greeks, though she was not widely worshipped among the Greeks because she overlapped with Aphrodite. Texts that speak of her are far fewer than of Ishtar or Inanna but she is well attested to in Egyptian writings. In some English translations of the OT, they translate Ashtoreth as Astarte, however, the Hebrew spelling is clearly “Ashtoreth”. The Egyptian variant of Astarte was well known in Canaan but the native tongue of the people dictated whether she was called Ashtoreth or Astarte. The Hebrew and the Canaanites would have used the name Ashtoreth, as previously noted. That aside, here are the extant texts, from my resources, that speak of Astarte.

- The Legend of Astarte and the Tribute of the Sea [c. 1800 BCE] (COS 1.23)

- This legend survives only in fragments. It appears to be an Egyptian adaptation of Ishtar’s decent into the underworld, mixed with the Canaanite myth of the storm god defeating the sea deity. It is theorized that this adaptation is due to Egypt’s close relationship with Canaan and the Hittite empire. The text itself is in the Hittite language. There is an alternate version of the story in Hurrian which is better preserved and can be read at the following link (The Other Version of the Story of the Storm-god’s Combat with the Sea). In the Hurrian version Astarte is clearly associated with Ishtar as she is hailed from Nineveh.

- The Zukru Festival [c. 2000 – 1500 BCE loose guess] (COS 1.123)

- The Zukru festival is one of the few festivals that we have records for that are likely to be similar to Hebrew festivals. This one is from Emar, in Syria. The festival is in the first month of the calendar which is September on the modern calendar. Thus, it’s a harvest festival. However, this particular festival was only every seven years (technically 6 years. I will elaborate on this below). The festival does not really center around Astarte but it does give a good image of what an ancient celebration to the gods would look like. The festivals are rather complex. There is one that happens in year six for a select few gods. Then in year seven, there is a giant celebration that includes all of the 70 gods in the pantheon. There are offerings and animals sacrifices to all 70 deities. It takes days to do it all.

- The festival included a lot of animals being offered to a number of deities, such as Nintura, Bel, and Dagan and a procession through the streets to their temples. They also offered hand made foods like bread, cakes, and patties, as well as wine libations.

- Sadly much of the text is broken and it is difficult to make out anything specific being dedicated for Astarte.

- Elkunirsa and Asertu [c. 1600 – 1200 NCE] (ANET 519/COS 1.55)

- This Canaanite myth is a fragmented Hittite version that features both Ašertu and Astarte. Ašertu is the wife of El, just like Asherah (Ašerah).

- In the myth, Ašertu is wrapped up in a fight Ba’al. She threatens him with a spindle which is a common item for Canaanite women.

- Astarte comes into the story when she learns that Ašertu is going to do harm to Ba’al. When she learns this of this plot she turns into an owl (a ḫapupiš) and flies to warn Ba’al. This the origin of Ishtar or Astarte being pictured with bird feet or bird wings.

- The myth is a variant of the Ba’al cycle myth, by which Ba’al is killed, sent to the underworld and then revived. This explains the changing of the seasons. In Mesopotamia, there is no storm-god parallel to Ba’al so it is Inanna that went to the underworld, died, and arose. Some Mesopotamian icons show Inanna with wings as she rises from the underworld.

- The Myth of Astarte, The Huntress [c. 1600-1200 BCE] (KTU 1.92)

- This is one of the few Canaanite mythologies where Astarte is a protagonist.

- In this hunting myth, Athtart (Astarte) is hunting deer and bull with a spear. The spear was a common hunting weapon but is not typically pictured in icons of Ishtar.

Biblical References to “Ishtar”

Before reading the biblical references, it’s important to remember that Ishtar went by multiple names. The name Inanna was used in ancient Sumer. During the rise of the Assyrian empire the name Ishtar became associated with the goddess. It should be noted that Sumerian and Akkadian are not the same languages which accounts for the name change. The Egyptians used the name Astarte. The Hittites worshiped Sauska. The Canaanites of the Bible worshiped Ashtoreth, the same goddess worshiped by the Phoenicians and Philistines. Every culture had a female deity comparable to Ishtar and even shared a similar mythology, so as one culture became prominent, their version of the goddess also became prominent.

The name most common in the Bible is not Ishtar, but Ashtoreth. This should be no surprise as the Israelites owe much of their culture to the Canaanites and Phoenicians, even their alphabet. The connection between Ashtoreth and Asherah is not fully known, if it exists at all. Many believe they are the same deity but it is hard to know since the Bible says so little about her. However, Asherah does appear in Canaanite literature and she is mentioned as the consort of both El and Yahweh. She is also seen as the mother goddess, similar to the consort of Sumerian Anu, Ki. This is why many scholars debate whether or not she can really be a parallel with Ishtar. Ishtar was a grand-child of Anu. She was never a mother-goddess, despite her association with fertility cults. However, since the Canaanite religions so thoroughly mixed and matched deities with various other deities, I will include passages about Asherah. The biblical texts appear to treat Ashtoreth and Asherah as the same figure. it is possible that she morphed a bit over the course of biblical history. Recall that the Old Testament covers hundreds of years. A of lot cultural changes happened in that time period.

Ashtereth was usually known as the female consort of Baal, however, at various times she was even described as the consort of Yahweh. However, it was for more common to ascribe the consort role to Asherah, who was more associated with the god El or Elyon. Both Asherah and Ashtoreth appear in the Old Testament.

For Solomon went after Ashtoreth the goddess of the Sidonians, and after Milcom the abomination of the Ammonites. (1 Kings 11:5)

The people of Israel again did what was evil in the sight of the Lord and served the Baals and the Ashtaroth, the gods of Syria, the gods of Sidon, the gods of Moab, the gods of the Ammonites, and the gods of the Philistines. And they forsook the Lord and did not serve him. (Judges 10:6)

So the people of Israel put away the Baals and the Ashtaroth, and they served the Lord only. (1 Samuel 7:4)

And the king defiled the high places that were east of Jerusalem, to the south of the mount of corruption, which Solomon the king of Israel had built for Ashtoreth the abomination of the Sidonians, and for Chemosh the abomination of Moab, and for Milcom the abomination of the Ammonites. (2 Kings 23:13)

Now therefore send and gather all Israel to me at Mount Carmel, and the 450 prophets of Baal and the 400 prophets of Asherah, who eat at Jezebel’s table.” (1 Kings 18:19)

The following passages show the only clear demonstration of an Ishtar cult within Israel. However, I will again repeat the fact that they did not know Ishtar. They knew her as Asherah, Ashtoreth, or other variants. Thus there is no reason to believe that the name for Easter came from the Ishtar cult because the Ishtar cult was already changed to the Asherah and Ashtoreth cult. But we can tell that certain features of the Ishtar cult was retained because in Ezekiel 8:14 there mention of Tammuz which is the Canaanite version of Damuzi. Additionally, the ritual of weeping for Damuzi’s death appears to be in place at Jerusalem.

The cakes made for the queen of heaven, in Jeremiah, refers to the ancient ritual of offering raisin cakes to Ishtar. In Canaan it was common to make offerings and libations to the moon goddess at monthly intervals. Thus, the Sumerian cake offerings was combined with Canaanite rituals. Most likely the deity known as the queen of heaven is Ashtoreth, not Asherah. Ashtoreth was a goddess of love and war, just like Ishtar. They were both called the queen of heaven, as well. As mentioned earlier, Asherah was simply a mother goddess.

The children gather wood, the fathers kindle fire, and the women knead dough, to make cakes for the queen of heaven. And they pour out drink offerings to other gods, to provoke me to anger. (Jeremiah 7:18)

Thus says the Lord of hosts, the God of Israel: You and your wives have declared with your mouths, and have fulfilled it with your hands, saying, ‘We will surely perform our vows that we have made, to make offerings to the queen of heaven and to pour out drink offerings to her.’ Then confirm your vows and perform your vows! (Jeremiah 44:25)

Then he brought me to the entrance of the north gate of the house of the Lord, and behold, there sat women weeping for Tammuz. (Ezekiel 8:14)

With these passages in mind, we can make a couple inferences about biblical worship of Ishtar.

- Her name was Ashtoreth, not Ishtar.

- The veneration of Asherah is not necessarily the same as the veneration of Ashtoreth.

- The only ritual associated with this goddess that we can find in the bible is cake offerings and the mourning ritual for Tammuz. No Easter-like celebration is know in the Bible or extant texts from the ANE.

- The Jewish response to the Ashtoreth cults was severe. After the reforms of Josiah it is probable that her veneration ceased for the most part in Canaan.

Why Ishtar Could NOT Be The Source For Easter

In previous posts on this topic, such as, The Origins of Easter, I explain this issue with great detail. However, I will summarize the argument here.

Ishtar, as we know her from the biblical texts, is not called Ishtar. She is known by the Israelites as either Astarte, Ashtoreth, or (as some have argued) Asherah. Are they speaking of the same goddess? Yes, for the sake of not opening another discussion about the transient nature of titles in the ancient near east, let us just generally say that these 3 goddesses were the same or similar. What is the mechanism by which a celebration to this goddess becomes the Christian version of Easter? What I mean to say is, where it the connection with Easter since none of these goddesses are named Ishtar? If not in name, then certainly in the symbology, right?

This is where most expositors display a large void in their understanding of history. They never actually explain what Easter was before the New Testament era. Where in history can we find anything similar to our Easter celebrations? And why isn’t it in any of the ANE or OT records? A number of pagan deities show up in the OT but not Ishtar, nor a celebration ascribed to her. One must simply invent this tradition out of thin air to make the story fit. Additionally, Ishtar was an Assyrian/Babylonian goddess who all but disappeared after the Persians took control of the Levant (C. 550 BCE). Additionally, the Persians were essentially Zoroastrians who had no belief in a Queen of heaven or any other goddess. They were not propagating any Ishtar cult.

Thus, about 500 years before Christ, Ishtar (who was never directly associated with Canaanite religion) was all but removed from history. This is evident by the dating of the many text that bear her name. Of the extant references to Ishtar none of them post-date the rise of the Persian empire. Moreover, when the Greeks took power Ishtar was replaced with Aphrodite. When the Romans took over they introduced an entirely different cult. The name Ishtar was simply not in use at Jesus’ time, or even within 200 years of the NT. No celebration dedicated to her existed either. Lastly, the proponents of the Ishtar=Easter view have to provide an explanation for why the only NT reference to Easter (Acts 12:4) does not actually say Easter. In Greek the text says “το πασχα” which means “the Passover”. There is no “Easter” in the NT texts.

The Passover was actually celebrated by the Jews and by early Christians. The reason why the KJV rendered it as Easter was because Christian Easter and Passover were synonymous in the first century of the church and the NT was written for Christian audiences. It was a stylistic translation. It was not pointing to a pagan festival having anything to do with Ishtar.

Moreover, the months dedicated to Ishtar and the mourning of Tammuz are September and July (keeping in mind that the lunar calendar doesn’t line up with the Gregorian months). The festivals known to celebrate Ishtar are during the harvest season, not the spring time. Also, the ANE didn’t celebrate spring like we have in the west. A large portion of the ANE only experiences two seasons, not four seasons. The idea of a spring time festival is virtually unknown. The closest thing would have likely been a planting season.

Symbols Associated with Ishtar

The traditional symbols of Easter are springtime themed. They abound with reflections of new life. We are used to seeing eggs, bunnies, flowers, etc. Could it be that this was carried over from the Babylonian worship of Ishtar? Of all the extant texts and references of Ishtar or her various other names, none of them have anything to do with bunnies, eggs, or spring. The best connection that exists is Ishtar’s role as a fertility goddess, but the symbols associated with her fertility cult are usually x-rated. There are no bunnies or eggs.

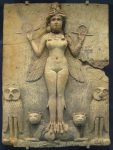

Traditionally, Ishtar was pictured with the following symbols, all of which are derived from the mythological stories about her. Those stories are listed above.

- A ring (measuring line) and a rod

- Bird wings and/or feet

- A lion

- A seductive woman

- 8 pointed star, on or off of her staff

- A staff with two snakes on it

- Swords, usually near the bird wings

These symbols associated with Ishtar can be seen in the many images made of her that have been found. Some of them can be seen below.

Ancient Representations of Ishtar

If Easter Doesn’t Come From Ishtar, then where?

The Easter bunny and the eggs come from a later pagan religion. There are European religions who did celebrate spring time and had traditional symbols of spring time, such as eggs, baby animals, new flowers. These were common among European religions because they had a winter, spring and summer. The cultures that worshiped Ishtar we in a drastically different climate where spring time was not such of a phenomenon or even something to be celebrated. The seasons celebrated by the cultures in the ancient near east are related to life in an agrarian society. They celebrated the harvest, the new moons, the rainy seasons, etc. There was no sense of springtime as it was known in colder climates, where all manner of new life would suddenly appear and the cold would thaw.

The traditional spring time festival that Christians know is actually from the Germanic, Norse and Northern European cultures. They had a goddess named Eoster, Ostara, or Eastre. She was often pictured with wreaths of flowers around her and all the traditional signs of spring, such as bunnies, birds, and sunshine. She was a goddess much celebrated in the cold climates because the coming of spring is always a celebration even when it’s not connected to religion.

The introduction of pagan Easter and it’s combining with Christian Easter/passover is described well by the 10th century monk, Saint Bede.

Eosturmonath has a name which is now translated “Paschal month”, and which was once called after a goddess of theirs named Eostre, in whose honour feasts were celebrated in that month. Now they designate that Paschal season by her name, calling the joys of the new rite by the time-honoured name of the old observance.

(The reckoning of time, tr. Faith Wallis, Liverpool University Press 1988, pp.53-54)

Thus, it appears that Easter as we know it was derived from Europe, not the ancient near eastern goddess Ishtar. The adoption of this goddess is explained by H.A. Guerber, in the 1909 book “Myths of the Norsemen”.

Saxon goddess Eastre, or Ostara, goddess of spring, whose name has survived in the English word Easter, is also identical with Frigga, for she too is considered goddess of the earth, or rather of Nature’s resurrection after the long death of winter. This gracious goddess was so dearly loved by the old Teutons, that even after Christianity had been introduced they retained so pleasant a recollection of her, that they refused to have her degraded to the rank of a demon, like many of their other divinities, and transferred her name to their great Christian feast. It had long been customary to celebrate this day by the exchange of presents of coloured eggs, for the egg is the type of the begin ning of life ; so the early Christians continued to observe this rule, declaring, however, that the egg is also symbolical of the Resurrection. In various parts ofGermany, stone altars can still be seen, which are known as Easter-stones, because they were dedicated to the fair goddess Ostara. They were crowned with flowers by the young people, who danced gaily around them by the light of great bonfires, a species of popular games practiced until the middle of the present century, in spite of the priests denunciations and of the repeatedly published edicts against then.

Conclusion

There is no connection between Ishtar, her cult, her iconography, or her mythology, with anything related to the Easter celebration. Ishtar was a goddess of love and war, not springtime. Her cult practiced sacred prostitution in ancient Sumer but was on the brink of extinction by the time the Persians conquered the Levant. Even then, there were no springtime festivals for her, as the month dedicated to Ishtar was in the fall, September/October in the Gregorian calendar. She is never pictured with eggs or bunnies or any traditional Easter iconography.

Pronounce the “I” like a long “E” (as is done in many latin based languages) and make the “H” silent (as is also done in many languages.) Now Ishtar sounds exactly like Easter. But no, they aren’t related at all. You folks will argue the most inarguable arguments. It is obvious that Easter is progeny of Ishtar. Nobody except maybe the most gullible of Christians believe you.

2 words sounding similar is not proof that they are the speaking of the same thing. For example, “bomber” in English means a war pilot while “bombero” in Spanish means fireman.

The word “Easter” is a northern European word from the Germanic language family, who knew nothing of Ishtar. They did, however, have a legend about a nymph named Eostre. Although, this legend is really hard to prove as well.

One thing is for sure, there was no use of the word Easter until the church migrated into Europe.

The main reason Passover was replaced with Easter was antisemitism. Constantine said at the council of Nicaea when he forbid the observance of Easter at Passover time, ‘It is unbecoming that on the holiest of festivals we should follow the customs of the Jews; henceforth let us have nothing in common with this odious people.’

That is a fact!

Thanks for your work here!

Yes, but also remember that the first century church observed the Eucharist of the broader “passover” primarily on Sunday which came to be called Easter Sunday. The quartodecimans observed it on Nisan 14 of which included Polycarp, but the majority of Christians at this time (Late first century and early 2nd century) observed the eucharist on Sunday. Paganism was not even an argument that Polycarp used when discussing this difference with Anicetus who kept it on Sunday. Still Polycarp and Anicetus parted as friends after taking the Eucharist together to show unity and both said it was not a salvational matter. However, Polycarp would have said it was a salvational matter if paganism was the origin or influencer. Instead, paganism was not part of the conversation. All the church fathers werevery strong against paganism and there is no way they would have abided a pagan celebration.

There is a number of places in the New Testament that was changed to draw & or deceive YHWH’S chosen ones away from the Torah, which is his Instructions on how to live in this world & to Love him with all of your Heart. It is impossible for God to Lie stated in the Book of Hebrews. So why is it that they changed the word Pascha in Acts 12:4 to the word Easter. Passover in the year that Yeshua was crucified was on a Wednesday and not on Friday. This was done to mislead people into thinking something other than the Truth. YHWH said not to Add or Takeaway from his Word. There is a number of other deceptions in the New Testament, for instance there is a number of times that the words quote” First Day of the Week” unquote, the word for week is Sabbaton and not week. If you were a Biblical Hebrew Scholar, why would you change SABBATON to WEEK. Also the word DAY is not in the Sentence at all, check it out. If these so called Bible Scholars were Born Again from Above, why would they be deceiving people. Think about it. I can give you a lot more like this, I have been doing this for a long time. Shabbot

Thanks for reading. For the most part, the vast majority of translation problems are usually cleared up by understanding the biblical languages. In the case of translating sabbaton as “week” rather than “sabboth”, it was just a matter of understanding the use of sabbaton as an idiomatic expression. There are numerous examples of the sabbaton being used to refer to a 7 day period. One that comes to mind is Paul’s instructions to the church on Corinth for collecting the money to be sent to the Jewish church. The use of sabbaton here implies “sabboth week”. Since the sabboth was every 7 day, it is no surprise that is became a short hand expression for “week”. I do not find this to be controversial.

1 Cor 16:2

On the first day of every week(sabbaton), each one of you should set aside a sum of money in keeping with your income, saving it up, so that when I come no collections will have to be made.

Acts 20:7 might be an even better example as the grammar make “week” the only logical translation.

“And upon the first day of the week(sabbaton), when the disciples came together to break bread, Paul preached unto them, ready to depart on the morrow; and continued his speech until midnight.”

Yea, right. Youre funny. The devil’s minions are DESPERATE.

It is usually best practice to make it obvious who you’re replying to and a specific example of what you’re disagreeing with. Merely insulting unnamed people isn’t very effective.

Great piece ! Thank you !

So then I have a question. Where did the idea of the Saxon Goddess Ostara come from? Could it have not been yet another cultures recycling of a much older Inanna?

Thanks for reading!

The origin of Oestre isn’t well documented, mostly because the difficulty of maintaining parchment and other writing substrates in a humid and unforgiving climate.

There are a number of germanic inscriptions from the 1st and 2nd centuries that mention Oestre as Austria-henea. She’s a fairly typical spring time fertility goddess and is accompanied by standard European springtime symbols.

As to whether or not she could be a rehashed version of Inanna I would say not much of a chance. Inanna/Ishtar was a goddess that was from the ancient Near East and her cult, for the most part, died with the civilizations that worshipped her. The last civilization to worship Ishtar was the Babylonian empire and they were almost completely erased by the Persians, Geeks, and Romans. The chances that a cult icon from a dead civilization would manifest in a region thousands of miles away that already had there own cult is slim. Additionally, there is little evidence that northern Europe had exposure to Near Eastern culture. Most cases of religious syncretism occur when one culture supplants another. Culture mixing from distant locations without large scale contact is relatively unheard of. Lastly, Ishtar wasn’t a springtime goddess. Her festival was at harvest in the fall. She wasn’t associated with any of the Oestre symbols like eggs and bunnies. She had her own set of symbols like a measuring line, owl claws, ect.

Hope that helps. Further questions always welcome.