The Events

Many Christians have grown up hearing about the Exodus story and it’s many sub-narratives. Some of the sub-narratives, such as the sea crossing and the calf incident are so well-known that even people outside the Abrahamic faiths are familiar with the events. When I was a child and I learned the calf-worship episode, I was struck by how quickly the people abandoned YHWH but I was also confused about why in the world they would worship a calf. As a modern American we are so disconnected from ancient cultures that some parts are simply inexplicable. However, the golden calf is quite understandable to the ancient world. In this article I will be explaining both the system of idol worship in the ancient Near East as well as why a calf was specifically selected for worship.

Before we get into an explanation, let’s also re-familiarize ourselves with the passage from Exodus 32.

Now when the people saw that Moses delayed to come down from the mountain, the people assembled around Aaron and said to him, “Come, make us a god(אֱלֹהִ֗ים) who will go(יֵֽלְכוּ֙) before us; for this Moses, the man who brought us up from the land of Egypt—we do not know what happened to him.” 2 Aaron said to them, “Tear off the gold rings which are in the ears of your wives, your sons, and your daughters, and bring them to me.” 3 So all the people tore off the gold rings which were in their ears and brought them to Aaron. 4 Then he took the gold from their hands, and fashioned it with an engraving tool and made it into a molded metal calf; and they said, “These(אֵ֤לֶּה) are your gods(אֱלֹהֶ֙יךָ֙), Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt.” 5 Now when Aaron saw this, he built an altar in front of it; and Aaron made a proclamation and said, “Tomorrow shall be a feast to Yahweh. 6 So the next day they got up early and offered burnt offerings, and brought peace offerings; and the people sat down to eat and to drink, and got up to engage in lewd behavior.

7 Then the Lord spoke to Moses, “Go down at once, for your people, whom you brought up from the land of Egypt, have behaved corruptly. 8 They have quickly turned aside from the way which I commanded them. They have made for themselves a molded metal calf, and have worshiped it and have sacrificed to it and said, ‘These are your gods, Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt!’” 9 Then the Lord said to Moses, “I have seen this people, and behold, they are an obstinate people. 10 So now leave Me alone, that My anger may burn against them and that I may destroy them; and I will make of you a great nation.”

11 Then Moses pleaded with the Lord his God, and said, “Lord, why does Your anger burn against Your people whom You have brought out from the land of Egypt with great power and with a mighty hand? 12 Why should the Egyptians talk, saying, ‘With evil motives He brought them out, to kill them on the mountains and to destroy them from the face of the earth’? Turn from Your burning anger and relent of doing harm to Your people. 13 Remember Abraham, Isaac, and Israel, Your servants to whom You swore by Yourself, and said to them, ‘I will multiply your descendants as the stars of the heavens, and all this land of which I have spoken I will give to your descendants, and they shall inherit it forever.’” 14 So the Lord relented of the harm which He said He would do to His people.

15 Then Moses turned and went down from the mountain with the two tablets of the testimony in his hand, tablets which were written on both sides; they were written on one side and the other. 16 The tablets were God’s work, and the writing was God’s writing engraved on the tablets. 17 Now when Joshua heard the sound of the people as they shouted, he said to Moses, “There is a sound of war in the camp.” 18 But he said,

“It is not the sound of the cry of victory,

Nor is it the sound of the cry of defeat;

But I hear the sound of singing.”(Exodus 32:1-18)

In this article I will seek to explore answers to a two main questions. Is the calf a physical replacement for Moses or for YHWH? Is there a significance to the idol specifically being a calf? In order to answer these questions a lot of ground will be covered. Therefore, some tertiary questions will be explored along the way.

Who’s Being Replaced; Moses or YHWH?

The Case for YHWH

At first glance the story tends to lend itself to the idea that the calf was designed to take the place of YHWH. After all, they did worship (bow down/וַיִּשְׁתַּֽחֲווּ) to it. But that in itself isn’t great evidence for a deity replacement, as I will explain in the next section. However, there are some interesting suggest found in the Hebrew phrasing of the passage that point towards a deity replacement. The phrasing in Exodus 32:1, 4 & 7 has been notoriously difficult to translate into English so many versions differ. In verse 1, Aaron is asked to make a “god” (singular) who will go before them. In verses 4 & 8, Israelites refer to the calf in a plural form saying “these are your gods, Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt!“. The difficulty arises in the use of plural and singular words; specifically for referencing the calf and how many gods are being mentioned. The physical calf idol is always referred to as a single entity. There is no more than 1 calf ever being mentioned. But when speaking of what the calf represents a plural is used. The calf represents the god(s), a plural form. To demonstrate the issue let us look deeper at both examples.

Exodus 32:1 – god or gods?

Come, make us a god(אֱלֹהִ֗ים) who will go(3mp/יֵֽלְכוּ֙) before us (Exodus 32:1)

This(cp/אֵ֤לֶּה) are your god(אֱלֹהֶ֙יךָ֙), Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt. (Exodus 32:4)or

Come, make us gods(אֱלֹהִ֗ים) who will go(3mp/יֵֽלְכוּ֙) before us (Exodus 32:1)

These(cp/אֵ֤לֶּה) are your gods(אֱלֹהֶ֙יךָ֙), Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt. (Exodus 32:4)

Either translation of אֱלֹהִ֗ים as “god” or “gods” can technically be correct. It can be translated as god, God, or gods. The context dictates the translation. Exodus 32:1 is made difficult with the verb “will go” because it’s a 3rd person, masculine, plural construction. It’s the way you would conjugate a verb for multiple people or subjects performing the action. It is not usually the case that a singular god is described as behaving in the plural. For example, in Exodus 20:2 YHWH says to Israel “I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery“. In this instance the verb “brought/הוֹצֵאתִ֛יךָ” is in the singular form, even though God is in the plural. In Deuteronomy 5:6 the same usage of “brought/הוֹצֵאתִ֛יךָ” as a singular verb is found. A similar use is found in Genesis 15:7 when God references bringing Abram out of Ur.

I am the LORD your God, who brought(2ms) you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery. (Deuteronomy 5:6)

Thus, it would seem probable that the request by the Israelites to make them a god is referring to an idol that represents multiple gods. Perhaps we could call it a “royal we” type of representation.

A similar issue appears in Exodus 32:4 with the use of pronouns. The pronouns “this” or “these” are very interchangeable, even though numerical mismatches do happen from time to time. We have two options for interpreting Exodus 32:4. The first option is that the plural form was used to indicate multiple gods. That is certainly a sensible conclusion. The other option is that the plural form was only used for grammatical purposes because אֱלֹהִ֗ים is plural construction. Given that verse 32:1 seems to be referring to multiple gods it is likely that the same is meant in 32:4. A true translation of “אֱלֹהֶ֙יךָ֙ אֵ֤לֶּה” must read “these [are] your gods”. A similar passage with the singular pronoun is found in Deuteronomy 1:21.

See, the Lord your God has given(3ms/נָתַ֨ן) you the land. Go up and take possession of it as the Lord, the God of your ancestors, told(3ms/דִּבֶּ֨ר) you. (Deuteronomy 1:21)

Given the translation pattern in similar verses it seems probable that the Israelites were looking to create new gods. However, the problem remains that they only created a single calf and referred to it as multiple gods. This is a difficult puzzle. However, we must not forget that monotheism was a later invention. The early Israelites did not believe in a single god but many gods. this form of henotheism was pantheon based and contained a power structure. Just like a head of household, the head of the pantheon could act as a representative for the other gods. In this way, the idol could be indirectly representative of the gods, even though it was a single object. Likewise, it could also represent a single deity who happens to be the representative for the pantheon. This idea we will follow up on later when we explore what specific deities were given bovine iconography.

The Case for Moses

There have been a few scholars that have questioned whether or not the Israelites meant to replace the Lord (YHWH) or replace Moses. A first reading might make it seem rather obvious that it cannot be Moses. However, I think the idea has a lot of merit but takes some background knowledge about ancient idol worship to understand the argument. The most obvious indicator for this theory is that the episode seemed to have been triggered by Moses’ prolonged disappearance. Furthermore, once the calf is formed they said “These are your gods, Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt!“, which seems to imply that there was some connection between being lead out of Egypt and the calf. Additionally, they demanded someone who would “go before us” implying the entity would continue to lead them as Moses did. The suggestion is that, perhaps, the Israelites associated Moses with YHWH so closely that Moses was seen as a manifestation of YHWH or his divine representative. After all, what they witness Moses do so far was nothing a mere mortal could do on their own.

When the Israelites request for Aaron to make them a God to go before them, it is not immediately clear what they mean by “gods”. Are they speaking of a physical idol alone or something with divine attributes? The Hebrew word “אֱלֹהִ֗ים” has a much wider semantic range than most people realize. In fact, it was common for idols to be called by the name of a god. The carved idols of both Ba’al and Asherah in the OT are referred to as Baals and Asherim (Asherim is the Hebrew plural form for Asherah), rather than “Baal idols” or “Asherah idols”. Thus, one could refer to an image of Ba’al as simply a Baal or multiple images as Baals.[1]Asherim, https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/ancient-cultures/ancient-israel/asherah-and-the-asherim-goddess-or-cult-symbol/ Is it possible that the calf idol was referred to as gods just like Baals and Asherim were? In other words, can the word “gods” simply be referring to the physical image and nothing more? This is an important question because if “אֱלֹהִ֗ים” is only referring to the physical idol, then the divine figure represented by the idol is could nearly limitless. But how large really is the semantic range of the word “אֱלֹהִ֗ים”? To answer that we must understand the origin of the word.

Elohim (אֱלֹהִ֗ים) in its most ancient form (El) refers to a Canaanite/Phoenician deity. El’s 70 sons were often referred to as the אֱלֹהִ֗ים (elohim/gods), because they were the sons of El. The word אֱלֹהִ֗ים here is essentially a plural version of the title, El (although its more complicated than that). It might sound silly but we have similar idioms in the English language. When one has children it is not uncommon for someone to refer to them by the name of a parent. For example, if a friend (we will call him Joseph for the example) has multiple children one might refer to them as little Josephs (or Joseph-im in Hebrew). As previously mentioned, we see this also in the use of the words Baal and Asherah in the Old Testament. Shrines and idols dedicated to such deities were often declared Baals and Asherim (Judges 2:11; 1 Samuel 7:4, Judges 10:10, 1 Samuel 7:4, 1 Kings 18:18, etc.). Thus, there is a long running precedent of referring to objects associated with a deity by the plural form of that deity’s name.

Even more interesting, the title אֱלֹהִ֗ים often refer to angels and messengers of YHWH. We don’t see it in the English translations but it’s explicit in the Hebrew texts. In fact, even the translators of the Septuagint (LXX) sometimes translated אֱלֹהִ֗ים as angels. Hebrew passages from Exodus 21:6, Exodus 22:8, Psalm 8:5, etc., and others, are examples of this phenomenon. Therefor, there is a case to be made that Moses was thought of as an אֱלֹהִ֗ים or a surrogate of YHWH. If true, then replacing Moses (the elohim) with a calf (elohim) is not that far fetched.

An interlude about idols in the ancient world

But how could an inanimate object (a calf or any other) replace the living Moses? That is where some knowledge of how idols functioned in the ancient world is needed. There seems to be a general idea that ancient people worshipped idols as deities. It might seem to be the most logical conclusion in the modern mind but that was not the function of idols in the ancient world. Idols were created to be inanimate objects for sure. But it was believed that a deity could come and inhabit the idol. Thus, the idol is both a representation and dwelling of sorts. It was not until the time of the prophets that people believed the idols to be actual deities. This idea is capture a number of times in the Bible, even though in non-biblical texts it is clear that they were thought of as only be indwell by a deity.

The idols of the nations are silver and gold, made by human hands. They have mouths, but cannot speak, eyes, but cannot see. They have ears, but cannot hear, nor is there breath in their mouths.

(Psalm 135:15-17)All who make idols are nothing, and the things they treasure are worthless. Those who would speak up for them are blind; they are ignorant, to their own shame. Who shapes a god and casts an idol, which can profit nothing? People who do that will be put to shame; such craftsmen are only human beings. Let them all come together and take their stand; they will be brought down to terror and shame. The blacksmith takes a tool and works with it in the coals; he shapes an idol with hammers, he forges it with the might of his arm. He gets hungry and loses his strength; he drinks no water and grows faint. The carpenter measures with a line and makes an outline with a marker; he roughs it out with chisels and marks it with compasses. He shapes it in human form, human form in all its glory, that it may dwell in a shrine. He cut down cedars, or perhaps took a cypress or oak. He let it grow among the trees of the forest, or planted a pine, and the rain made it grow. It is used as fuel for burning; some of it he takes and warms himself, he kindles a fire and bakes bread. But he also fashions a god and worships it; he makes an idol and bows down to it. Half of the wood he burns in the fire; over it he prepares his meal, he roasts his meat and eats his fill. He also warms himself and says, “Ah! I am warm; I see the fire.” From the rest he makes a god, his idol; he bows down to it and worships. He prays to it and says, “Save me! You are my god!” They know nothing, they understand nothing; their eyes are plastered over so they cannot see, and their minds closed so they cannot understand. No one stops to think, no one has the knowledge or understanding to say, “Half of it I used for fuel; I even baked bread over its coals, I roasted meat and I ate. Shall I make a detestable thing from what is left? Shall I bow down to a block of wood?” Such a person feeds on ashes; a deluded heart misleads him; he cannot save himself, or say, “Is not this thing in my right hand a lie?”

(Isaiah 44:9-20)

The exilic and 2nd temple period saw a serious crusade among the Hebrews to stamp out the practice of idol worship and convert to the true monotheism, or at least a proper henotheism with YHWH at the head. As a result, we see more dialogues in the scriptures about the worthlessness of idols, explaining how a manmade object is useless. However, cultures who worshipped using idols also knew they were worthless, that is, until a deity entered and dwelt in it. Ancient cultures in the Near East actually believed that the idols were empty and useless, but that particular rites would enable the chosen deity to embody the idol. The idol served a similar purpose as the Israelite Holy of Holies. With the proper care and cleanliness the deity would dwell with its people. This relationship had many perks for the deity, such as food and rest.

We can see this in practice in the late story found in the Apocryphal text of Daniel 14 but is often separated as its own book called “Bel and the Dragon”. The story of Daniel and the idol named Bel exposes what was a common practice in the ancient world; the practice of priests making an idol appear to be alive. This was needed to keep the religion alive. But it really only benefited the priests and their families.

Now the Babylonians had an idol called Bel, and every day they provided for it twelve bushels of choice flour and forty sheep and six measures of wine. The king revered it and went every day to worship it. But Daniel worshiped his own God.

So the king said to him, “Why do you not worship Bel?” He answered, “Because I do not revere idols made with hands, but the living God, who created heaven and earth and has dominion over all living creatures.”

The king said to him, “Do you not think that Bel is a living god? Do you not see how much he eats and drinks every day?” And Daniel laughed, and said, “Do not be deceived, O king, for this thing is only clay inside and bronze outside, and it never ate or drank anything.”

Then the king was angry and called the priests of Bel[b] and said to them, “If you do not tell me who is eating these provisions, you shall die. 9 But if you prove that Bel is eating them, Daniel shall die, because he has spoken blasphemy against Bel.” Daniel said to the king, “Let it be done as you have said.”

Now there were seventy priests of Bel, besides their wives and children. So the king went with Daniel into the temple of Bel. The priests of Bel said, “See, we are now going outside; you yourself, O king, set out the food and prepare the wine, and shut the door and seal it with your signet. When you return in the morning, if you do not find that Bel has eaten it all, we will die; otherwise Daniel will, who is telling lies about us.” They were unconcerned, for beneath the table they had made a hidden entrance, through which they used to go in regularly and consume the provisions. After they had gone out, the king set out the food for Bel. Then Daniel ordered his servants to bring ashes, and they scattered them throughout the whole temple in the presence of the king alone. Then they went out, shut the door and sealed it with the king’s signet, and departed. During the night the priests came as usual, with their wives and children, and they ate and drank everything.

Early in the morning the king rose and came, and Daniel with him. The king said, “Are the seals unbroken, Daniel?” He answered, “They are unbroken, O king.” As soon as the doors were opened, the king looked at the table, and shouted in a loud voice, “You are great, O Bel, and in you there is no deceit at all!”

But Daniel laughed and restrained the king from going in. “Look at the floor,” he said, “and notice whose footprints these are.” The king said, “I see the footprints of men and women and children.”

Then the king was enraged, and he arrested the priests and their wives and children. They showed him the secret doors through which they used to enter to consume what was on the table. Therefore the king put them to death, and gave Bel over to Daniel, who destroyed it and its temple.

(Bel and the Dragon 3-21)

The story of Bel and the Dragon reflects a tradition rooted in ancient idolatry but not identical to the form of idolatry known to the ancient Hebrews in the desert. The man-made idol was not believed to be the deity itself. It was merely a vessel. Thus, it could be destroyed and the deity unaffected. Moreover, a deity could embody multiple idols at once. Ancient Mesopotamian texts describe idol worship in a slightly different light than what we see in the exilic and 2nd temple Hebrew writings. One ancient text from the Hittite region (NW of Canaan) recounts how a new convert worshiping the “Goddess of the Night” can build and dedicate an additional temple to her. The ritual text describes the building of the temple, its implements, and how to draw the spirit or essence of the deity into the additional new idol and temple.

If a person becomes associated with the Deity of the Night in some temple of the Deity of the Night and if it happens that, apart from that temple of the Deity of the Night, he builds still another temple of the Deity of the Night, and settles the deity separately, while he undertakes the construction in every respect:

The smiths make a gold image of the deity. Just as her ritual (is prescribed) for the deity, they treat it (the new image) for celebrating in the same way. Just as (it is) inlaid 5 (with) gems of silver, gold, lapis, carnelian, Babylon–stone, chalcedon, quartz, alabaster, sun disks, a neck (lace), and a comet of silver and gold — these they proceed to make in the same way

……

On the day on which they take the waters of purification, (they attract) the previous deity with with red wool and fine oil along seven roads and seven paths from the mountain, from the river, from the plain, from heaven and from the earth.

On that day they attract (lit., pull) (the deity). They attract (lit. pull) her into the previous temple and bind the uliḫi to the deity (’s image). The servants of the deity take these things:

(The Context of Scripture[2]William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger, The Context of Scripture (Leiden; New York: Brill, 1997–), 173-174.)

The ritual goes on to describe an elaborate ritual of “pulling” and attracting the deity to the new temple and image using expensive colored yarns and food offerings. Similar rituals likely existed for other ancient Near Eastern deities which is assumed by the fact that more famous deities like Ishtar had as few as 7 temples dedicated to her. In these temples both priests and royals could meet with the divine presence of their deity. These religious concepts were not unique to Mesopotamian religions. Similar idols and temples existed in Canaanite/Israelite religion. One such temple existed in northern Canaan dedicated to the deity El and his divine sons, the Elohim. Smaller places of worship existed in locations like Bethel (house of El). Archaeological findings have confirmed a number of shrines in northern Canaan dedicated to the Israelite deity El which contained simplistic versions of the Mesopotamian idols. One of the more recently studied shrines is located at Tel Arad and I encourage the reader of this article to google the many publicly available archaeological reports on this site.

I bring all this up to make a point which is that ancient religion in the Levant, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia (basically the entire Near East) practiced some form of idolatry in which the deity inhabited various objects, including man made idols. Another fascinating ancient text describing the ritual of attracting a deity to indwell an idol goes by the name of the “Mouth Opening” or “Mîs-pî”. This ceremony describes in detail how an idol is created from scratch and the process for attracting the deity to dwell in it. Some scholars such as Amy L. Balogh and Joshua M. Matson have written on the matter, suggesting that both the calf incident and Moses’ calling parallel the Mouth Opening ritual. Matson suggests that the biblical authors appear to be contrasting the making of the calf in Exodus 32:1-6 with the making of Moses in Exodus 3, arguing that Moses was a superior bearer of the divine than the calf. However, these parallels are not widely accepted by mainstream academia nor another Old Testament scholars.

Why a Calf?

If the Hebrews were making an idol for their deity to dwell in, or even to replace Moses, why a calf? Why not a lion or an adult ox? Both images were abundant in ancient religions. There are two very realistic answers to this question. The first is that the cow was a common symbol for Israelite people and the Hebrew text is being generic and not precise. In other words, calf and bull are interchangeable. However, a bull-cow is not the same as a calf and I don’t think the authors were being careless. The second possible answer is that the calf specifically represented a particular deity.

A number of people have pointed out that there was a calf deity (Apis) in Egyptian religion and the Israelites were leaving Egypt so it’s probable that there is an Egyptian connection. Apis was occasionally pictured with a crescent moon, which will become important later in this section, however, Apis was not worshipped via idolatry.[3]Daily Offering Ritual in ancient Egyptian temples In fact, Egyptians did not practice idolatry like the Canaanites and Mesopotamians did. While they did make images, they did not believe in the notion that such an image would be indwelled by the deity. Additionally, Apis was closely associated with the Pharaoh, the very demigod that the Israelites were escaping from. For these reasons, it seems unlikely that the escaping Israelites would create an idol representing an Egyptian deity. Nevertheless, the association of the moon with a calf is an important and universal connection in the ancient Near East.

Calf as a Symbol in Canaanite Religion

The ancient Canaanite religion was replete with descriptions of El as an Ox or a bull (CTA1:22, 30, CTA 2:30-35, CTA 4:120). Neighboring cultures in Mesopotamia also honored the high gods with bull images. Ishtar was often called the wild ox of heaven (ETCSL t.1.3.2, KTU 1.92, COS 1.173). The image of an ox or bull was reserved for high deities as they are the most powerful common animal in the region. It was such a common image that the letter A in semitic languages was derived from the symbol of the ox head. The ox allowed humans in the ancient Near East to plant crops in a rather difficult location. Farming was somewhat reliant on the strength of the ox.

Nevertheless, the passage in Exodus clearly describes a calf and not a mature bull/ox. But a number of lesser deities (children of El) were actually associated with a calf. The most common was Nanna/Sin the moon god. Interestingly, moon worship was abundant in Canaanite and Mesopotamian religion. Nanna is described in Sumerian texts as the “Calf of Enlil”. Of course, Enlil was often represented as an adult bull, so it would make sense that his offspring was described as Enlil’s calf. The calf is also connected with the moon deity through symbology. The crescent moon was often connected to the crescent shaped calf horns. In Mesopotamia religion the moon deity, Nanna, is said to be a keeper of the flocks and had many of his own.[4]The Herds of Nanna, https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.4.13.06# The connection between calves and the moon deity seems to play a role in the exodus narrative.

Such, worship of calves in Canaanite and Israelite religion is seen a few times in the Bible. Jeroboam is recorded as mimicking the Judean harvest feast of Sukkot by setting up calf idols and demanding them to be worshipped on the 15th day of the 8th month.

And Jeroboam appointed a feast on the fifteenth day of the eighth month like the feast that was in Judah, and he offered sacrifices on the altar. So he did in Bethel, sacrificing to the calves that he made. And he placed in Bethel the priests of the high places that he had made.

(1 Kings 12:32)

The significance of the date should not be overlooked as this was a significant day in moon cults. The 1st day, 7th day, and 15th day were all recognized in Canaan as special days. The 1st day of the month is that day of the new moon cycle. The 7th was sacred because the moon was 1/2 way to its zenith and 7 was a sacred number by itself. The 15th day of the month was very special because the moon was full and in its greatest part of the cycle. Jeroboam’s feast day being in the middle of the month was placed directly on the full moon and incorporated calves.

Even more interesting, the passover feast (commemorating the exodus event) began on the 15th day of the month. The Passover connection to the moon cycle is lauded to in Psalm 81 and Exodus 12.

The animals you choose must be year-old males without defect, and you may take them from the sheep or the goats. Take care of them until the fourteenth day of the month, when all the members of the community of Israel must slaughter them at twilight. Then they are to take some of the blood and put it on the sides and tops of the doorframes of the houses where they eat the lambs. That same night they are to eat the meat roasted over the fire, along with bitter herbs, and bread made without yeast. Do not eat the meat raw or boiled in water, but roast it over a fire—with the head, legs and internal organs. Do not leave any of it till morning; if some is left till morning, you must burn it. This is how you are to eat it: with your cloak tucked into your belt, your sandals on your feet and your staff in your hand. Eat it in haste; it is the Lord’s Passover.

(Exodus 12:5-12)Sound the ram’s horn at the New Moon,

and when the moon is full, on the day of our festival;

this is a decree for Israel,

an ordinance of the God of Jacob.

When God went out against Egypt,

he established it as a statute for Joseph.

(Psalm 81:3-5)

Thus, there might be a connection to the full moon with the passover. Is it possible that the full moon exodus of Israel inspired the creation of the calf? It is very possible as some might rightly assume the moon deity played a role in the passover and exodus events. It is also significant that the entire Hebrew calendar is based on the lunar cycle and appears to be copied from Mesopotamian culture. This would make sense considering the early Canaanites practiced a religion very similar to the Mesopotamians which included the Mesopotamians moon deities. Below is a layout of the Babylonian and Hebrew calendars, both based on the lunar cycle.

| Babylonian Calendar | Hebrew Calendar |

|---|---|

| Nīsannu | Nīsān |

| Ayyāru | Iyyār |

| Sīmannu | Sīwān |

| Duʾūzu | Tammūz |

| Ābu | Āb |

| Ulūlū | Elūl |

| Tašrītu | Tišrī |

| Araḫsamna | Marḥešwān |

| Kisilīmu | Kislēw |

| Ṭebētu | Ṭēbēt |

| Šabāṭu | Šebāṭ |

| Addāru | Adēr |

In addition to the aformentioned Canaanite customs, the worship of the moon deity can be traced back to ancient Mesopotamia and the migration of Abraham’s relatives. It has been suggested that Abraham’s father, Terah, was named after the moon which is “yeraḥ/יָרֵחַ”. Terah was from Ur [of the Chaleans] who had a fully functioning moon cult with temples and offerings. Even today a partial temple exists there dedicated to the moon deity. It is known as the Zuggurat of Ur. Joshua 24 alludes to the previous religious practices of Abraham and his family.

And Joshua said to all the people, “Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel, ‘Long ago, your fathers lived beyond the Euphrates, Terah, the father of Abraham and of Nahor; and they served other gods.

(Joshua 24:2)

Baal and his counterparts outside Canaan

Another deity associated specifically with the calf was Baal because he was the son of the high god, El. Naturally, the children of El (the bull) are referred to as calves. Baal worship was popular in northern Canaan as well as the regions north of Canaan. This popular storm deity was the highest ranking child of the high god. In Ugaritic mythology Baal obtain his position by delivering the council of the gods from his evil sibling, Mot. Mot was the god of death and was often accompanied by Tiamat, the deity of the sea and chaos. Although he was not alone in his battle, as he was helped (and saved) by his sister Anat. Both Baal and Anat were considered to gods of war and thus, by proxy, gods of deliverance. Baal, however is the one who is closely associated with his father, the bull, making Baal a calf. Ugaritic imagery of Baal, however, only haphazardly associates Baal with the calf (as opposed to the bull). The distinction between calf and bull is hard to make just using images. The image show on the left (or above if on mobile) shows Baal with small calf horns but other images of Baal contain bull imagery.

An interesting Anatolian inscription exists outside the old Hittite city of Hatussa which shows the high deity Teshub leading the pantheon of gods next to his son Sharruma. The imagery is accompanied by text describing Sharruma as the “calf of Teshub”.[5]Fleming, Daniel E., and דניאל א’ פלמינג. “אם אל הוא פר, מיהו עגל? / IF EL IS A BULL, WHO IS A CALF? REFLECTIONS ON RELIGION IN SECOND-MILLENNIUM … Continue reading Sharruma is the Hittite/Hurrian version of Baal. It’s nearly the same mythology but with different names. As we will see, a storm god being the son of the high god who is pictured as a bull is ubiquitous throughout the ancient Near East.

Another neighbor of Canaan, Syria, also had a storm god that was the favored son of the high god. His name was Hadad/Adad or haddu. His association with Baal was so close that eventually the two deities merged into a single deity named Baal-Hadad. Hadad’s father was the high Mesopotamian god, An/Anu, although other local traditions make him the son of Enlil, one of the sons of An. Nevertheless, Hadad is often pictured with calf or bull figures. The Mesopotamian and Canaanite imagery is not as clear as what is seen in the Hittite description, showing the storm god clearly as a calf of the high deity.

The Babylonian deity Marduk was also pictured with calf and bull icons. He was the son of the local Sippar high god, Utu/Shamash and is described as the “bull calf of the sun god Utu”.[6]Ringgren, Helmer (1974), Religions of The Ancient Near East, translated by John Sturdy, The Westminster Press He is also called the “Calf of the storm” but his association as a storm god is not well attested to in Babylon.[7]Abusch, T. 1999. “Marduk.” In Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, ed. K. van der Toorn, P. Becking, and P.W. van der Horst, pp. 543-549. Leiden: Brill. This is likely because of how different the geography and weather was in Babylon VS its neighbors to the west. Like Baal, Marduk gained his position in the pantheon by defeating the watery chaos and the serpent who serves the sea deity.

Certainly more could be said about the relationship between calves and high ranking second generation deities like Baal and Marduk. Nevertheless, it is clear that the calf was a symbol of the strong waring deities who were the younger and more vigorous of the deities. Their parent deities were often more associated with strength, justice, creation, and wisdom. Hence the imagery of a high deity as a bull and their offspring as a calf is and easy connection.

Cult of Yaho and the Bull

While scholars have known for some time about the use of bull imagery in northern Canaan and its neighbors, less is known about whether or not YHWH was commonly associated with a bull. Nevertheless, archaeological evidence exists demonstrating that Yahwism retained some of the bull and calf imagery from Canaanite religion. The difficulty presented by the association of Yahwism and Elohism is that it can be hard to know which came first. They shared many overlapping themes. Either way, an early 3rd century BCE (or late 4th century) text named Papyrus Amherst 63 shows that even as late as the hellenistic period there was cult activity in northern Canaan that associated YHWH with the calf and bull image. However, the document purports to be describing events from the 20th Egyptian Dynasty (1189 BC to 1077 BC.). Papyrus Amherst 63 also demonstrates a connection between the Yaho cult, bulls, and the moon.

Yaho humiliates the lowly one.

They have mixed the wine in our jar,

In our jar, at our New Moon festival!

Drink, Yaho,

From the bounty of a thousand bowls!……..

Behold, as for us, my Lord, our God is Yaho!

May our Bull be with us.

May Bethel answer us tomorrow.

Some have suggested that such use of the bull in Yahwism was a result of a carryover from Israelite religion. However, we cannot know at this point if the biblical text about the calf was written as a later polemic against the northern Israelites. The general consensus among scholars is that bull imagery was applied to Yahwism once it supplanted Elohism.

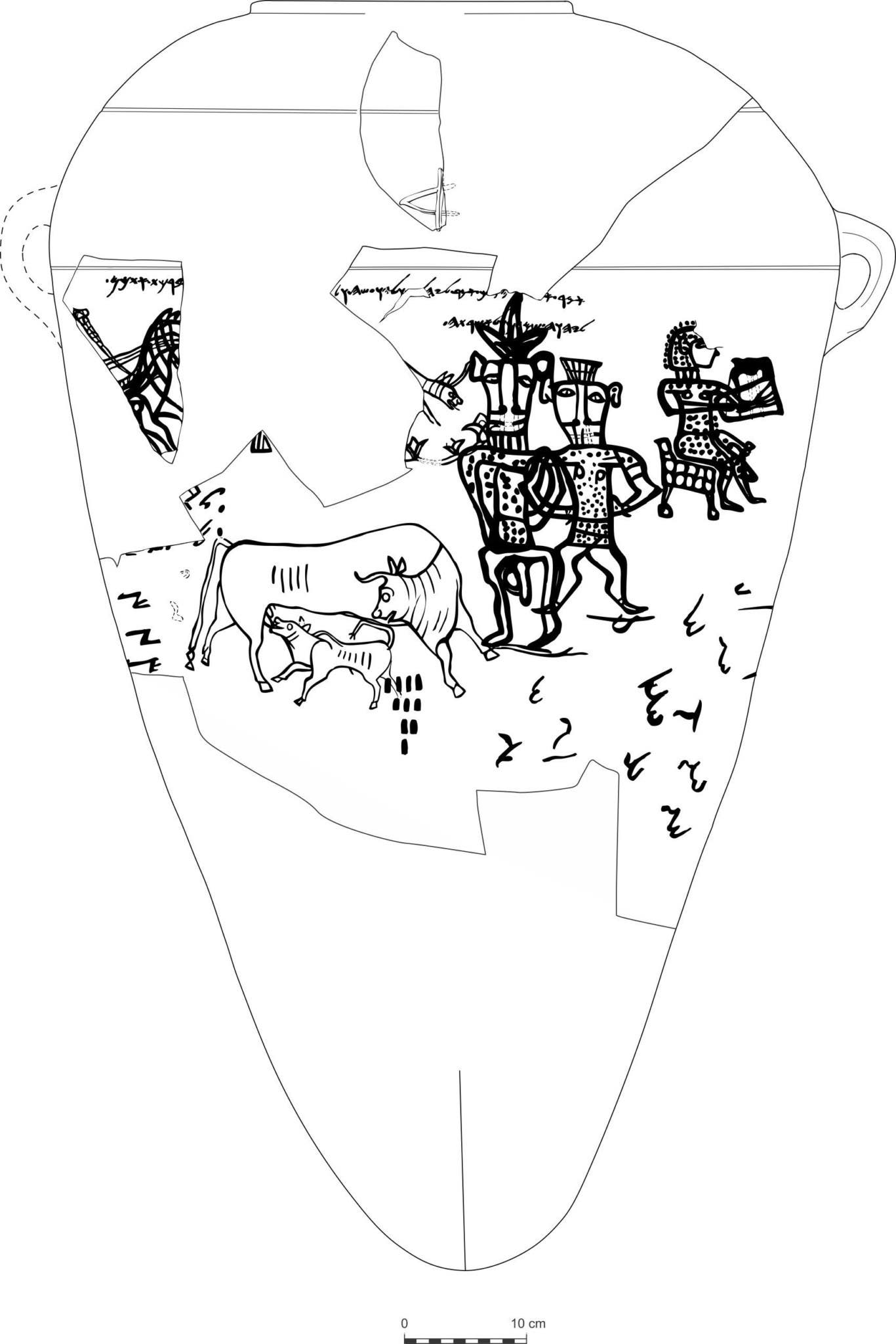

There are, however, older evidences of the connection between bulls and calves with YHWH. An artifact known as the Samaria Ostraca, which dates from about 750-850 BCE, where we find the name Egelyo which means “calf of Yahweh”. The name Egelbol also appears which translates to “calf of Baal”. The association of Baal, Yahweh, and El with the bull was not uncommon. [8]Leroy Waterman, “Bull-Worship in Israel”, The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literature, Volume XXXI 1915, pp. 235 Another ancient inscription shows Yahweh and Baal together, alongside Asherah and some bovine depictions. Commonly known as the Kuntillet`Ajrud, this inscription dates back to the 8th or 9th century BCE.

The translation of the inscription is sometimes debated but reads as follows:

… by YHWH of Teman [and] by Asheratah. Everything that he could ask from someone, the Father and Mother graciously gave him. He requested, so YHW[H] gave him what he desired.

What we see in the pottery inscription is YHWH and Baal standing next to a bull and a calf. The most obvious conclusion is that YHWH and Baal are being represented by a bull and a calf. In this case, Baal is the calf of YHWH. The astute observer at this point is asking the logical question: wasn’t Baal the son of El and not YHWH? This is a correct observation. However, this is why so many scholars believe Yahwism gradually replaced the worship of El and in doing so many parts of the religion were transposed from El to YHWH. Thus, it follows that the calf is Baal.

Conclusions

So, what does all this mean? It would appear that we can glean at least two important points from the exodus calf episode. The first is that the calf might not be replacing YHWH but rather Moses – in an attempt to manifest YHWH’s power since Moses was no longer available to do so. However, this theory is not without its problems. Currently, it seems more probable that the calf was meant as a manifestation of YHWH, Nanna, Baal, or another Baal-like deity. The second is that the calf was associated with the Canaanite religion, specifically the moon deity, Nanna/Sin. Additionally, archaeology has found a number of inscriptions associating YHWH with the moon cult and the bull calf. Many scholars believe that YHWH worship essentially supplanted El worship in Canaan which accounts for many overlapping themes. [9]Bull Worship in Israel Thus, given that the worship of both calves (and bulls) were an already established form of worship in the Canaanite and Mesopotamian cultures, there is no surprise that early Israelites maintained these practices.

In conclusion, the calf was likely either a generic relic of Canaanite religion or it was a specific deity such as Baal. The most likely of these two is that the calf was representing Baal and possibly other second-generation deities who had the power to deliver.

Additional Reading

Lloyd R. Bailey, “The Golden Calf“, Hebrew Union College Annual Vol. 42 (1971), pp. 97-115.

Leroy Waterman, “Bull-Worship in Israel“, The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literature, Volume XXXI 1915, pp. 229-255.

Mark S. Smith “Where the Gods Are: Spatial Dimensions of Anthropomorphism in the Biblical World”, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016.

Mark S. Smith, “The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel’s Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts” Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 2001.

Othmar Keel and Christoph Uehlinger, “Gods, Goddesses, and Images of God In Ancient Israel”, Minneapolis. Fortress Press. 1998.

Hundley, Michael B. “What Is the Golden Calf?” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 79, no. 4 (2017): 559–79.

William Dever, “Asherah, consort of Yahweh: new evidence from Kuntillet Ajrud” Bulletin of the AmericanSchools of Oriental Research 255 (1984).

References

| ↑1 | Asherim, https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/ancient-cultures/ancient-israel/asherah-and-the-asherim-goddess-or-cult-symbol/ |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger, The Context of Scripture (Leiden; New York: Brill, 1997–), 173-174. |

| ↑3 | Daily Offering Ritual in ancient Egyptian temples |

| ↑4 | The Herds of Nanna, https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.4.13.06# |

| ↑5 | Fleming, Daniel E., and דניאל א’ פלמינג. “אם אל הוא פר, מיהו עגל? / IF EL IS A BULL, WHO IS A CALF? REFLECTIONS ON RELIGION IN SECOND-MILLENNIUM SYRIA-PALESTINE.” <i>Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies / ארץ-ישראל: מחקרים בידיעת הארץ ועתיקותיה</i> כו (1999): 23*-7*. Accessed September 11, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23629920. |

| ↑6 | Ringgren, Helmer (1974), Religions of The Ancient Near East, translated by John Sturdy, The Westminster Press |

| ↑7 | Abusch, T. 1999. “Marduk.” In Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, ed. K. van der Toorn, P. Becking, and P.W. van der Horst, pp. 543-549. Leiden: Brill. |

| ↑8 | Leroy Waterman, “Bull-Worship in Israel”, The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literature, Volume XXXI 1915, pp. 235 |

| ↑9 | Bull Worship in Israel |

What part was confusing for you?

Good grief, this is a lot of effort to come to a nonsensical point! Was your education money well spent?