Introduction

Most fans of biblical archaeology are familiar with the 2001 work, “The Bible Unearthed”, by Israel Finkelstein & Neil Asher Silberman. This powerful work takes on the great task of examining and interpreting archaeological data from various locations and time periods familiar to the Old Testament. Both of the authors, Finkelstein and Silberman, are world renown scholars and archaeologists. Many have pointed out what seems to be a liberal bent in their works and some have even suggested a form of antagonism towards the biblical records.

In “The Bible Unearthed” Finkelstein & Silberman argue that the rapid conquest model given by the Bible is actually incorrect. They posit that the archaeological evidence supports a slow infiltration of Semites in the land, possibly even an internal uprising. Either way, the biblical model is called into question. The difficult part of interpreting archaeology is that sometimes the findings don’t confirm what was previously thought to be true. In some cases it seems to contradict biblical history. Certainly that has been true at times. Finkelstein & Silberman believe that this is one of the times that the Bible and archaeology great disagree. The book’s conquest summary concludes with the following statement:

Although we know that a group called Israel was already present somewhere in the Canaan by 1207 BCE, the evidence on the general political and military landscape of Canaan suggests that a lightning invasion by this group would have been impractical and unlikely in the the extreme.1

However, the issue with the conquest is not that the evidence contradicts the biblical account (even though it does in some places) but that our understanding of the biblical account is limited. I believe that this is the case with the history and archaeology concerning Israel’s emergence in the promised land. The problem with the conquest is not that the Bible is wrong but that many people are only reading summary passages rather than the whole story. Christians are just as guilty of this type of reading as are the critics.

If the common Christian was asked how Israel moved into the promised land, one would get a short story about a battle for Jericho, followed by a short summation about them taking over the rest of the land shortly after the fall of Jericho. This short explanation is probably derived from reading the Book of Joshua which tends to gloss over large pieces of history. In fact, one could say that it’s summary of Israel overtaking the land is misleading because in other parts of Joshua, the reader is told that they still had lands to conquer. The biblical conquest is anything but rapid. In fact, the bible give a time frame of 200-400 years for the conquest, depending on the date of the exodus.

In the following article I want to lay out a more robust picture of how the Bible describes the conquest. After that I will provide some archaeological finds that help to fill out the picture of the conquest. As with Finkelstein & Silberman I agree that the conquest was not a rapid invasion of military might. I disagree that the Bible describes a rapid conquest. While selected readings would lead one to think that a rapid conquest was described by the Bible, when the rest of the related passages are included a very different picture emerges.

The Biblical Story

When Jabin king of Hazor heard of this, he sent word to Jobab king of Madon, to the kings of Shimron and Akshaph, 2 and to the northern kings who were in the mountains, in the Arabah south of Kinnereth, in the western foothills and in Naphoth Dor on the west; 3 to the Canaanites in the east and west; to the Amorites, Hittites, Perizzites and Jebusites in the hill country; and to the Hivites below Hermon in the region of Mizpah. 4 They came out with all their troops and a large number of horses and chariots—a huge army, as numerous as the sand on the seashore. 5 All these kings joined forces and made camp together at the Waters of Merom to fight against Israel. (Joshua 11:1-5)

………..

12 Joshua took all these royal cities and their kings and put them to the sword. He totally destroyed them, as Moses the servant of the Lord had commanded. 13 Yet Israel did not burn any of the cities built on their mounds—except Hazor, which Joshua burned. 14 The Israelites carried off for themselves all the plunder and livestock of these cities, but all the people they put to the sword until they completely destroyed them, not sparing anyone that breathed. 15 As the Lord commanded his servant Moses, so Moses commanded Joshua, and Joshua did it; he left nothing undone of all that the Lord commanded Moses.

16 So Joshua took this entire land: the hill country, all the Negev, the whole region of Goshen, the western foothills, the Arabah and the mountains of Israel with their foothills, 17 from Mount Halak, which rises toward Seir, to Baal Gad in the Valley of Lebanon below Mount Hermon.He captured all their kings and put them to death. 18 Joshua waged war against all these kings for a long time. 19 Except for the Hivites living in Gibeon, not one city made a treaty of peace with the Israelites, who took them all in battle. 20 For it was the Lord himself who hardened their hearts to wage war against Israel, so that he might destroy them totally, exterminating them without mercy, as the Lord had commanded Moses.

21 At that time Joshua went and destroyed the Anakites from the hill country: from Hebron, Debir and Anab, from all the hill country of Judah, and from all the hill country of Israel. Joshua totally destroyed them and their towns. 22 No Anakites were left in Israelite territory; only in Gaza, Gath and Ashdod did any survive.

23 So Joshua took the entire land, just as the Lord had directed Moses, and he gave it as an inheritance to Israel according to their tribal divisions. Then the land had rest from war. (Joshua 11:12-23)

List of Defeated Kings

12 These are the kings of the land whom the Israelites had defeated and whose territory they took over east of the Jordan, from the ArnonGorge to Mount Hermon, including all the eastern side of the Arabah:

2 Sihon king of the Amorites, who reigned in Heshbon.

He ruled from Aroer on the rim of the Arnon Gorge—from the middle of the gorge—to the Jabbok River, which is the border of the Ammonites. This included half of Gilead. 3 He also ruled over the eastern Arabah from the Sea of Galilee[a] to the Sea of the Arabah (that is, the Dead Sea), to Beth Jeshimoth, and then southward below the slopes of Pisgah.

4 And the territory of Og king of Bashan, one of the last of the Rephaites, who reigned in Ashtaroth and Edrei.

5 He ruled over Mount Hermon, Salekah, all of Bashan to the border of the people of Geshur and Maakah, and half of Gilead to the border of Sihon king of Heshbon.

6 Moses, the servant of the Lord, and the Israelites conquered them. And Moses the servant of the Lord gave their land to the Reubenites, the Gadites and the half-tribe of Manasseh to be their possession.

7 Here is a list of the kings of the land that Joshua and the Israelites conquered on the west side of the Jordan, from Baal Gad in the Valley of Lebanon to Mount Halak, which rises toward Seir. Joshua gave their lands as an inheritance to the tribes of Israel according to their tribal divisions. 8 The lands included the hill country, the western foothills, the Arabah, the mountain slopes, the wilderness and the Negev. These were the lands of the Hittites, Amorites, Canaanites, Perizzites, Hivites and Jebusites.

9 the king of Jericho

the king of Ai (near Bethel)

10 the king of Jerusalem

the king of Hebron

11 the king of Jarmuth

the king of Lachish

12 the king of Eglon

the king of Gezer

13 the king of Debir

the king of Geder

14 the king of Hormah

the king of Arad

15 the king of Libnah

the king of Adullam

16 the king of Makkedah

the king of Bethel

17 the king of Tappuah

the king of Hepher

18 the king of Aphek

the king of Lasharon

19 the king of Madon

the king of Hazor

20 the king of Shimron Meron

the king of Akshaph

21 the king of Taanach

the king of Megiddo

22 the king of Kedesh

the king of Jokneam in Carmel

23 the king of Dor (in Naphoth Dor)

the king of Goyim in Gilgal

24 the king of Tirzah

thirty-one kings in all.

What is often overlooked in the conquest discussion is Joshua 13. Interestingly, Joshua 13 appears to directly contradict Joshua 11:23.

So Joshua took the entire land, just as the Lord had directed Moses, and he gave it as an inheritance to Israel according to their tribal divisions. Then the land had rest from war. (Joshua 11:23)

Just a few passages later, the book of Joshua declares that the land was not entirely taken, as the Lord directed Moses.

Land Still to Be Taken

13 When Joshua had grown old, the Lord said to him, “You are now very old, and there are still very large areas of land to be taken over.

2 “This is the land that remains: all the regions of the Philistines and Geshurites, 3 from the Shihor River on the east of Egypt to the territory of Ekron on the north, all of it counted as Canaanite though held by the five Philistine rulers in Gaza, Ashdod, Ashkelon, Gath and Ekron; the territory of the Avvites 4 on the south; all the land of the Canaanites, from Arah of the Sidonians as far as Aphek and the border of the Amorites; 5 the area of Byblos; and all Lebanon to the east, from Baal Gad below Mount Hermon to Lebo Hamath.

6 “As for all the inhabitants of the mountain regions from Lebanon to Misrephoth Maim, that is, all the Sidonians, I myself will drive them outbefore the Israelites. Be sure to allocate this land to Israel for an inheritance, as I have instructed you, 7 and divide it as an inheritance among the nine tribes and half of the tribe of Manasseh.”

(Joshua 13:1-7)

What is the cause of this discrepancy? It’s likely due to the hand of multiple redactions over history. Of course, it’s not uncommon in ancient times to use bombastic language when recording military victories. In fact, Sennacherib described the king of Elam and the king of Babylon as defecating in their chariots over the fear of Sennacherib’s invasion.

the king of Elam and the king of Babylon, the fear of my mighty battle overcame them and they defecated in their chariots and they fled back to their lands in order to save their lives. (COS 2.119E)

In the telling of Sennacherib’s siege on Jerusalem, he refers to the conquest in a way very reminiscent to the summary passage in Joshua 11.

As for Hezekiah, the Judean,7 I besieged forty-six of his fortified walled cities and surrounding smaller towns, which were without number. Using packed-down ramps and applying battering rams, infantry attacks by mines, breeches, and siege machines, I conquered (them). (COS 2.119B)

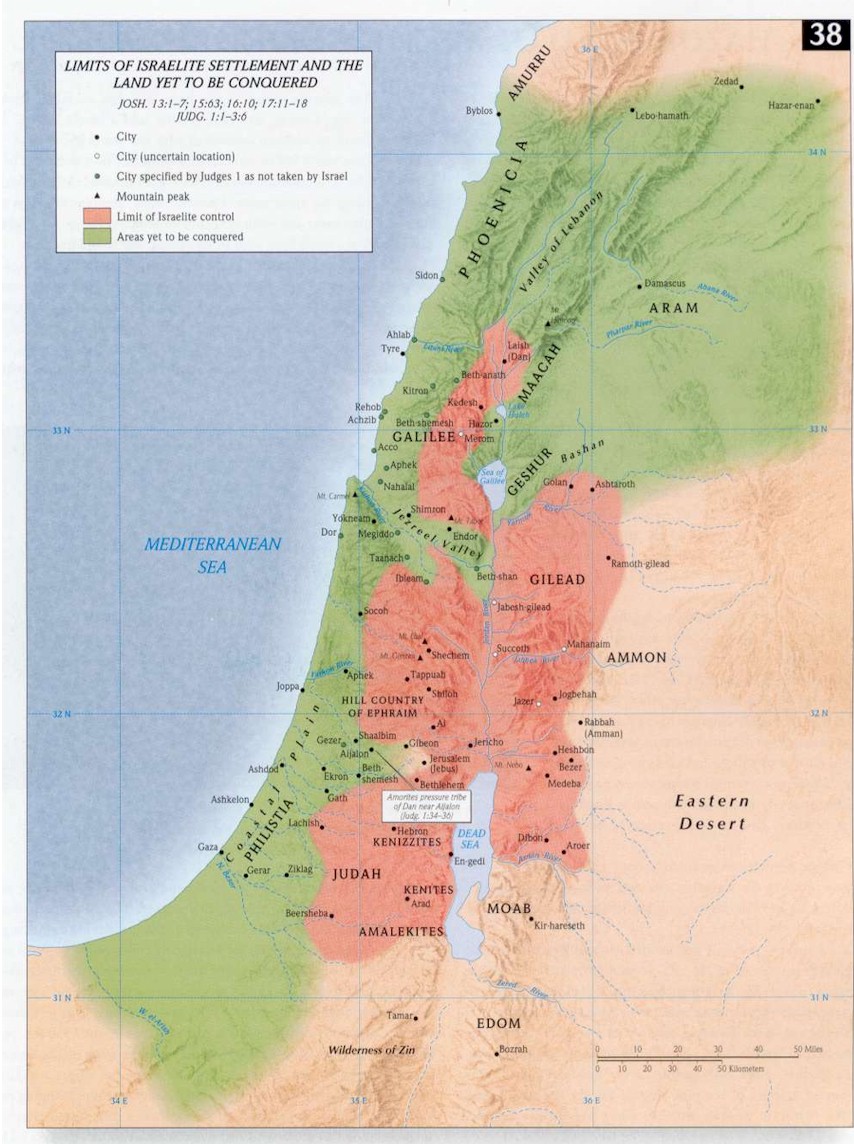

In summation, the conquest was not complete. Joshua 11 was either a poor redaction or possibly just a blown up summary statement attempting to make the Israelites appear more dominant than they really were. At the end of Joshua’s life, large portions of the land were yet to be conquered. Israel had conquered mostly just the highlands in south east Canaan. This area, surrounding Jerusalem and the Dead Sea, was only sparsely populated. Inversely, most of the major cities in Canaan were being supported by the Egyptian empire and eventually also by the great Hittite empire.

How Many Years Did It Take?

The Bible actually provides a fairly accurate testimony describing how long it took Israel to conquer various parts of the land. The first part of the calculation is derived by figuring out Joshua’s age. Joshua was likely about 30-40 years old leading up to the conquest.

I was forty years old when Moses the servant of the Lord sent me from Kadesh-barnea to spy out the land, and I brought word back to him as it was in my heart. (Joshua 14:7)

We know that Joshua was estimated to have died at age 110, based on the text the bears his name.

It came about after these things that Joshua the son of Nun, the servant of the LORD, died, being one hundred and ten years old. (Joshua 24:29)

Thus, Joshua and the Israelites battled for the land over a period of 70-80 years. However, as noted previously, there were still lands yet to be conquered. The author of Joshua states that “very large areas of land” still needed to be conquered.

When Joshua had grown old, the Lord said to him, “You are now very old, and there are still very large areas of land to be taken over.

“This is the land that remains: all the regions of the Philistines and Geshurites, from the Shihor River on the east of Egypt to the territory of Ekron on the north, all of it counted as Canaanite though held by the five Philistine rulers in Gaza, Ashdod, Ashkelon, Gath and Ekron; the territory of the Avvites on the south; all the land of the Canaanites, from Arah of the Sidonians as far as Aphek and the border of the Amorites; the area of Byblos; and all Lebanon to the east, from Baal Gad below Mount Hermon to Lebo Hamath. (Joshua 13:1-5)

We can go on to also read the book of judges and we will see that Israel fought decades and even centuries to acquire the rest of the land. One could argue that the rest of the land was not fully obtained until the reign of David which was around 1000-900 BCE. Assuming an early exodus date, that means the conquering of the land took roughly 300-400 years.

This slow conquest model appears to also be predicted by the Lord in the Pentateuch.

I will not drive them out from before you in one year, lest the land become desolate and the beasts of the field become too numerous for you. 30 Little by little I will drive them out from before you, until you have increased, and you inherit the land. 31 And I will set your bounds from the Red Sea to the sea, Philistia, and from the desert to the River. For I will deliver the inhabitants of the land into your hand, and you shall drive them out before you.

(Exodus 23:29-31)You shall not be terrified of them; for the Lord your God, the great and awesome God, is among you. 22 And the Lord your God will drive out those nations before you little by little; you will be unable to destroy them at once, lest the beasts of the field become too numerous for you. 23 But the Lord your God will deliver them over to you, and will inflict defeat upon them until they are destroyed. 24 And He will deliver their kings into your hand, and you will destroy their name from under heaven; no one shall be able to stand against you until you have destroyed them. 25 You shall burn the carved images of their gods with fire;

(Deuteronomy 7:21-25)

Based on what we can see from scripture, the Israelites did not finish the conquest of the land during Joshua’s life. They did not finish the conquest during the days of the judges either. In fact, the Book of Judges provides what is believed to be a far more accurate representation of how Israel conquered the land. Rather than large centralized campaigns, described in Joshua, Judges depicts small scale battles between one or more Israelite tribes and a neighboring locality. Indeed, the over-taking of the land was less of a conquest and more of an infiltration. It happened over such a large span of time that one could even say it looked like a home-grown infestation of guerrilla warfare. The book of Judges lists no less than 18 battles between various tribes of Israel and a surrounding tribe or people group.

Witness From Ancient Texts

The body of ancient texts during late Bronze Age (when the conquest began) is vast, however, not all of them are translated or accessible to the average person. Nevertheless, a number of very important text are readily available in English and are discussed below. One remarkable feature of texts from Canaanite locations is the rise of the deity called Yahweh. Once virtually unknown, Yahweh becomes a deity that nearly everyone in Canaan recognizes or worships. Another interesting feature is the migration of Semitic groups like the Hyksos, who were a dominant power in Egypt, into southern Canaan. This migration appears to be recorded in the Egyptian records. Both Josephus and Apion (1st century historians) believed the Hyksos migration to be the source of the exodus stories. The last feature of the ancient texts that deserves mention is the repeated mention of Canaanite infiltration by a group called the Habiru (also ‘apiru, ‘abiru, or hapiru). The Habiru were another Semitic group that arose to power during the later part of the late bronze age (3300 – 1200 BC) and the start of the iron age (1200 500 BCE). Whether or not these two groups were merged at any given time seems unknown.

Alalakh Texts & Census’

Some 70 census lists have been discovered in Alalakh which describe various people groups. While censuses are not typically riveting literature, they do provide great evidence for the existence of ancient peoples. One of the lists from Alalakh, (tablet 180) from the 1600s lists the ḫāpiru as being in the land, which most believe to be of semitic origin and part of the Hebrew people (not to be confused with Israelite people). Were these ḫāpiru peoples decedents of Abraham or relatives? It is hard to know. However, many have sought to connect the ḫāpiru with the Hebrew peoples. This group is characterized as being outside agitators and not well-liked by the natives. Assuming the Abrahamic tradition, this appears to be accurate. They were not natives is Canaan.

A contextual study on the texts from Alalakh can found read free online at jstor.org.

A more in-depth study of texts from Alalakh can be read and downloaded from the University of Chicago website (Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization).

Amarna letters

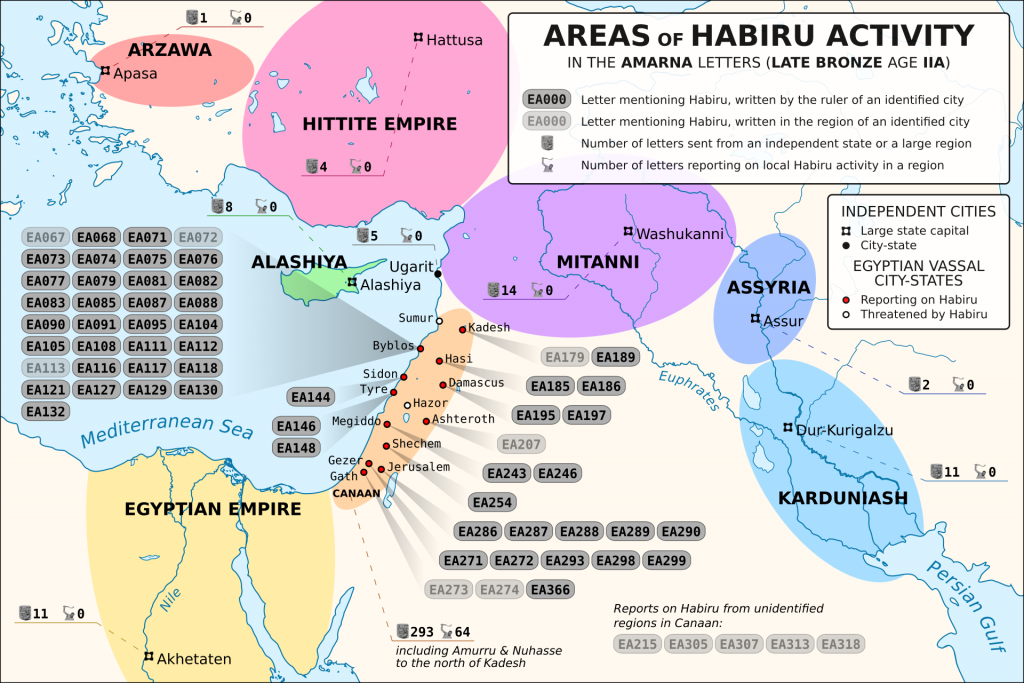

About 90% of the known tablets from Amarna have been translated into English and are accessible from various websites and books. In the letters, a number of Egyptian vassal states report to be under siege by the Habiru. In fact, over 200 reports are found just in the Canaanite cities. As noted in the graphic below, mentions of the Habiru are 99% from the land of Canaan, especially from southern Canaan.

In the letters, a number of kings write to the powers in Egypt asking for reenforcement for their cities, which are under attack. From reading other texts from the period, it seems as though these cities were being attacked by various groups of people simultaneously (not just the Israelites). The threat from multiple fronts would make it easier for these cities to fall or weaken. The Amarna letters specifically blame the ḫāpiru/Habiru for the destruction. However, we know that the Philistines were also infiltrating the land during the conquest.

One of the letters from Abdi-Heba, ruler of Jerusalem, which is dated to about 1340/1330 BCE, shows that the city was under siege by the ḫāpiru. In the letter, Abdi-Heba accuses Egypt of not coming to his aid. Abdi-Heba describes the situation as dire, with the surrounding lands already fallen in battle. This dating coincides with an early exodus date and the order of lands under siege during the conquest.

“Why do you love the ʿApiru but hate the mayors?” Accordingly, I am slandered before the king, my lord. Because I say,

“Lost are the lands of the king, my lord,” (EA 286)

In another letter to Egypt (c. 1350-1335 BC), king Adda-Danu of Gazru (Gezer) mentions to the Egyptian overlord that his city is being attacked by people from the mountains.

“There being war against me from the mountains.” (EA 292)

This seem to coincide with modern theory that the Israelites initially took up home in the mountains and hill country and then later infiltrated the cities. In the biblical account the Israelites emerge from the wilderness, not from within the cities or from other cities. The data appears to be agreeing with the Bible if an early exodus date is assumed.

Ugaritic texts

Despite not receiving much attention in the modern discussion of the conquest, Ugaritic texts are abundant and informative for understanding the social and political state of Canaan in the Late Bronze age. In a number of Ugaritic texts, Yahweh is mentioned, demonstrating that the name Yahweh was not exclusive to Israelite people, or that Israel was already in the land. One inscription mentioning Yahweh sounds quite similar to a famous Psalm;

“Who is your servant (but) a dog that my lord should remember his servant?” (COS 3.42)

“what is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him?” (Psalm 8:4)

The most remarkable thing about these Ugaritic texts mentioning Yahweh is that they are dated from the era just before the Babylonian exile, in the 6th century BCE. By this time the Israelites had already gained a united monarchy under David and then split under the rule of his grandchildren. However, the land of Canaan remained thoroughly Israelite in nature. This explains the worship of the Israelite God, Yahweh, even in locations that are not considered Israelite territory. Ugarit was on the border of Canaan and the Hittite Empire. By the 6th century the religion and culture of Israel had dominated the land for nearly 700 years.

It is clear from earlier Ugaritic texts that the primary deities in early Ugarit were Ba’lu, Baal, El, Asherah and a few other Canaanite deities. Yahweh is not mentioned in early Ugarit, only in late Ugarit texts. This suggests the rise of Yahweh’s people over the centuries.

Hittite Texts

Various texts from the late Bronze age, as well as other archaeological data, show that the Hittite people encountered a series of successive wars starting in the 13th-12th century BCE. Nevertheless, not all of the Hittite Empire fell. Remnants were able to hold out. In the end, the remaining Hittite powers were able to form an alliance with Egypt. Egypt was now fighting multiple wars and was eager to make peace in the Hittite regions. The Hittites eventually also enjoyed an alliance with the Babylonian Empire, giving them some semblance of strength after a lengthy period of destruction.2 Two Hittite texts from the Late Bronze era that demonstrate these relationships: the Letter from King Hattusili III to King Kadasman-Enlil of Babylon and the letter from Queen Naptera of Egypt to Queen Puduhepa of Hatti. In both letters, the leaders who are representing Hittite territories describe the land as being at peace and in good health. However, much destruction occurred in the years leading up to the alliances, and shortly after the alliance, the Hittites would be under attack again.

Destruction layers from Hattusa contain fire damage and letters from the period lay blame on “People of the Sea” (most likely Philistines or Phoenicians). In 1180 BCE the royal citadel of Biiyiikkale was completely destroyed. The destruction contains large amounts of fire damage. It was most definitely burned to the ground. The invasion of northern Canaan by the Israelites and the Sea Peoples was a nearly perfect storm, resulting in what some have called a dark age in the Syro-Hittite region.3 The fall of Biiyiikkale was by the hands of an unknown people. Given the invasion timing of the Sea Peoples and also the conquest by Israelites, the destruction of Biiyiikkale by two competing foes is entirely plausible. This would coincide with the many feuds Israel had with it’s neighbors which are recorded in the book of Judges.

The Israelite people, possibly along-side other Semitic groups, were not able to capture the Hittite territories. However, they were able to destroy a few locations. In the Bible, the Hittites were not defeated either.

Egyptian Texts

The Merneptah Stele is a monument erected by the Egyptian king, Merneptah, in approximately 1208 BCE. It is significant to the conquest debate because the monument names a people group in the land of Canaan named “Israel” connotated as a foreign people. The connotation in the text is often used of nomadic people groups. The Egyptian king said that he killed the seed of Israel, the foreign/nomadic peoples. At the time of the conquest of Canaan Israel would have most definitly been seen as both nomadic and foreign. It would be another 200 years before the tribes were united enough to gain a king to rule over the nation and build a recognized national power in the region.

Other Egyptian writings, describe, in detail, the expulsion of the Semitic peoples from Egypt who they called the Hyksos. Much has been made about the Hyksos as they were identified by Josephus and Apion as being the Semitic group that the Bible associates with the exodus.

“After the conclusion of the treaty they left with their families and chattels, not fewer than two hundred and forty thousand people, and crossed the desert into Syria. Fearing the Assyrians, who dominated over Asia at that time, they built a city in the country which we now call Judea. It was large enough to contain this great number of men and was called Jerusalem.”

(Josephus, Against Apion, quoting Manetho’s Aegyptiaca)

There is one problem with the Hyksos theory, which is that the expulsion was a century or more earlier than the biblical exodus. Some have proposed that the expulsion was not a one-time even but it was an on-going event, having multiple waves of expulsions. Nevertheless, the exodus mythology likely had some origin in these Semitic peoples being cast out of Egypt. We know from Egyptian annals that many Semitic slaves were taken from Canaan in the middle Bronze Age. So much so that the population was cut nearly in half.4

Other texts

One early text, from the 9th century BCE mentions Yahweh and surprisingly to some, his “asherah”. The letter from Ashyaw the king descries asherah as a female partner to Yahweh, which was not an uncommon idea in ancient Canaan.

“Say to Yehallel and to Yawʿasah, ‘I bless you by Yahweh of Samaria and his asherah!’”

Interestingly, Yahweh is mentioned in connection with Samaria. The author of the letter was from Kuntillet Ajrud, a small location in the North East part of the Sinai Peninsula. A few other letters from this region exist that mention Yahweh and his asherah.5 The biblical account also describes the issue of asherah in Canaan. It would appear the the veneration of Yahweh’s consort was not a biblical construct but a real practice according to ancient texts.

Conclusions

Like many ancient texts, a central truth exists but it is surrounded by centuries of lore. The exodus of Semitic peoples from Egypt is not disputed. The dates are hard to pin down but it’s a known phenomenon. The slow rise of power by a group that worshiped Yahweh, within Canaan, also appears to agree with the biblical account. The notion that some have asserted, that the conquest was a short period, is a straw-man argument. The Bible and archaeology both agree that the rise of the Israelites took a 300-400 year period.

Additionally, history and the Bible agree that once the exiled people entered the land, they eventually stopped waging wars and intermarried with the natives. Not only that, but the infiltration of these peoples appear to have been from the mountainous regions. These are the same regions where the Bible describes the conquest having been successful.

The [conquered] lands included the hill country, the western foothills, the Arabah, the mountain slopes, the wilderness and the Negev. (Joshua 12:8)

The lands not conquered in the Bible were northern planes and coastal regions. These were held by the Philistines, Phoenicians, and Hittites. History also confirms this account.

A final point that needs attention is that in the century leading up to the end of the Bronze Age (c. 1177 BCE), every place from Egypt up to the Hittite Empire was ravaged by war and famine. This constant war amongst all the nations created a destruction so vast that a dark age was created. Populations were diminished. Cities were razed to the ground. Writings and inscriptions became more scarce. It was this vacuum of power and population that likely allowed the Israelites and other Semitic peoples to come from the hill country and wilderness and posses power in the land. The battles were for the major cities and Israel was largely living outside of these great cities. Once these cities were weakened, the invasion from the hills an villages was an easy task.

The Bible’s retelling of the rise of the Israelites is a sensationalized account which was normal for ancient histories. All of the identity texts and annals from the ancient near east are written with a certain amount of sensationalism. They downplay their loses and embellish their victories as well as the struggles which they had overcame. Other pieces of history usually get mixed into the story, such as the plagues on Egypt.

Much to the interest of Old Testament readers, the late Bronze Age did see a terrible plague of influenza. It was the likely cause of death for Pharaoh Akhenaten. It’s trail of death even made it into Canaan. Is it possible that this plague was the source seed of the Mosaic legend? Once can only guess. Even more curious is the practice of Canaanite city-state governance by Egypt. It was common for governors of Egyptian city-states located outside Egypt (such as Canaan) for the governor to be raised and educated in Pharaoh’s court.6

1 – Finkelstein, Israel, and Neil Asher Silberman. The Bible Unearthes: Archaeologys New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, 76.New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 2002.

2, 5 – Hoffner, Harry A., Jr. “A Fragmentary Blessing.” In The Context of Scripture: Monumental Inscriptions from the Biblical World, 172. Vol. II. New York, NY: Brill, 2000.

3 – Hawkins, J. D. “The Neo-Hittite States in Syria and Anatolia.” In The Cambridge Ancient History, edited by John Boardman, I. E. S. Edwards, N. G. L. Hammond, and E. Sollberger, 372-441. The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

4 – Knoll, K. L. Canaan and Israel in Antiquity: An Introduction. Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Academic Press, 2002.

6 – Knoll, K. L. Canaan and Israel in Antiquity: An Introduction, 119. Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Academic Press, 2002.

1 thought on “Does Biblical Archaeology Confirm Israel Conquering The Promised Land?”