If you ever wondered what bunnies and eggs have to do with Easter then you are not alone. Many have tried to connect Easter to various spring time celebrations and fertility festivals that have appeared in various cultures. The most popular Easter myth is that it stems from the festival dedicated to the goddess Ishtar. Given that Easter and Ishtar sound so similar it seems that these two would definitely be connected.

The theory suggests that the Romans carried over Easter celebrations dedicated to Ishtar which is why Easter is in the KJV and how Easter got it’s name. However, they have nothing in common. Below we shall discuss the actual origins of Easter and exactly why Ishtar has nothing to do with our Easter celebration.

Who is Ishtar?

Any spring time fertility festival dedicated to Ishtar is more mythical than real life. While it is true that Ishtar was a real Babylonian/Akkadian/Assyrian goddess and that they did indeed have celebrations for her, there is no real proof that it had any relation to eggs, bunnies, or any other modern Easter traditions.

The goddess Ishtar was one of the oldest deities in the Ancient Near East. Writings about her go back well beyond 2000 BCE. There were even rulers who took on the name Ishtar as a hyphenated title, such as Lipit-Ishtar, the fifth king of the First Dynasty of Isin, who ruled from 1934–1924 BCE. The Isin dynasty was a small ANE dynasty from the region of modern day Iraq. Inscriptions from the same region as late as the 5th century BCE also spoke of the the goddess Ishtar. Inscribed on a cylinder, from the Reign of King Nabonidus (556-539 BCE), are the military exploits of the king, who gives credit to various gods for his victories.

… I mustered my numerous troops, from the country of Gaza on the border of Egypt, (near) the Upper Sea on the other side of the Euphrates, to the Lower Sea, the kings, princes, governors and my numerous troops which Sîn, Shamash and Ishtar my lords had entrusted to me….. (Nabonidus Cylinder from Sippar)

Her original Mesopotamian identity was actually as Inanna, the daughter of Enki, who was the god of wisdom.

Ishtar has also acquired a few different names over the centuries in the east. Since she was adopted by multiple cultures and that language changes over time, Ishtar was known by the following names.

- Inanna (Earliest Sumerian attestation, circa 3500-2000 BCE)

- Ishtar (Common Mesopotamian and ANE title, circa 2500-500 BCE)

- Astarte (Used by Egypt and various cultures in the Canaanite region, 3000-? BCE)

- Ashtoreth (Mostly Canaanite usage and near surrounding cultures. Appears in the Bible often. Circa 2000-700 BCE)

- Athtar (Divergent Arabian version that changed many attributes of Ishtar. Circa 1500-500 BCE)

Even though her title identity changed from time to time, most later cultures knew her as the Princess Daughter of the king of the gods, An (or Anu). As daughter of the highest god, Ishtar was described as spoiled and often ill-tempered. She was told to have wild mood swings and exact cruel revenge on others. She had many lovers, though some of them did not turn out well in the end. Interestingly, certain Mesopotamian legends depict Ishtar as the earthly lover of Anu and not his daughter.

The later Mesopotamian and Akkadian/Assyrian myths thought of Ishtar as also an astral goddess. Ishtar was initially associated with the 6 pointed and then 8 pointed star. This is a very common symbol for her in the era of the biblical patriarchs. She later became associated with the planet Venus.

Every culture that adopted Ishtar (even the Egyptians as Astarte) assigned various roles to the goddess. One of the oldest witnesses to the identity of Ishtar is the mythical story of how Ishtar descended into the underworld (akin to Persephone in Greek culture). The legend has been told in multiple cultures and generations but the typical story is that Ishtar goes to the underworld and she is killed. After 3 days and nights she is revived by her rescuers and makes an escape. In various tellings of the story, she is freed by the ransom of her lover, Dumuzi. In various later stories her lover was named Tammuz, which is what we see in Ezekiel 8:14-15.

14Then he brought me to the entrance of the north gate of the house of the Lord, and I saw women sitting there, mourning the god Tammuz. 15He said to me, “Do you see this, son of man? You will see things that are even more detestable than this.” (Ezekiel 814-15)

It is the legend(s) of her going to the underworld which reveal the story behind some of her symbols. In one such story she descends with a measuring line and rod. To understand the bulk of her symbols one should read the “Epic of Gilgamesh“, “Erra and Ishum” and the “Descent of Ishtar“. These ancient legends are widely available upon a google search.

Additionally, the ancient city of Nineveh had multiple temples over their history that were dedicated to Ishtar. According to Mesopotamian legend, the fertile crescent housed 7 temples dedicated to Inanna (Ishtar). They conducted prayers and rituals as prescribed by ancient customs. One such prayer was recorded and saved in history stems from a much later date, in the Hittite region. In the poetry of the prayer, the writer is asking for Ishtar to bring favor upon them.

bring life, health, streng[th], longevity, contentment (?), obedience (and) vigor, (and) to the land of Ḫatti growth of crops (lit., grain), vines, cattle, sheep (and) humans

Other parts are more descriptive of a celebration dedicated to Ishtar which would have occurred in the spring, in which they ask (or conjure) the goddess to return to the temple.

As to whether or not festivals were attributed to Ishtar, there seems to be little evidence of such things. What evidence that does exist points more towards temple rituals, often in the form of prostitution. In some ANE cultures the function of the temple prostitute was created by Ishtar. The temples dedicated to Ishtar featured such women. In the Akkadian legend of “Erra and Ishum”, the city of Anu and Ishtar (they are lovers in this story) is called a “city of prostitutes”. Thus, what we actually know about the cultic practices associated with Ishtar are not at all related to any festivals but more towards an organized temple practice.(Citation)

The Symbols Associated with Ishtar

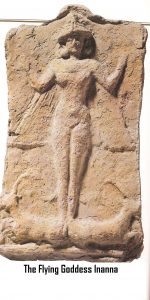

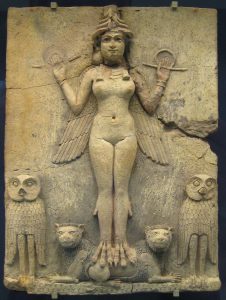

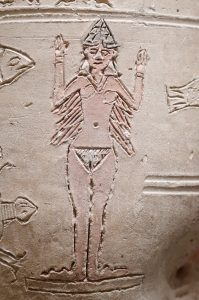

The modern myth about Ishtar that she was associated with eggs, bunnies, and the familiar Easter symbols, is simply false. While this is often repeated in church circles, it is not supported by any evidence. Since we have many carvings, engravings, and drawings of Ishtar, it’s easy to see what symbols she was associated with over the ages. Below is a list of various symbols she was known to be connected with.

- A ring (measuring line) and a rod

- Bird wings and/or feet

- A lion

- A seductive woman

- 8 pointed star, on or off of her staff

- A staff with two snakes on it

- Swords, usually near the bird wings

Some symbols that are best known come from the Burney relief carving which dates back to the 1800’s BCE. Her depiction seems to match an ancient inscription about her that very closely parallels the story above (the Descent of Ishtar). This version of the story describes what she is wearing, which can easily be seen in the carvings.

She placed the shugurra, the crown of the steppe, on her head.

She arranged the dark locks of hair across her forehead.

She tied the small lapis beads around her neck,

Let the double strand of beads fall to her breast,

And wrapped the royal robe around her body.

She daubed her eyes with ointment called “Let him come, let him come,”

Bound the breastplate called “Come, man, come!” around her chest,

Slipped the gold ring over her wrist,

And took the lapis measuring rod and line in her hand.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is depicts her wings and provides understanding of the serpents she is often depicted with.

Irkalla, the Queen of the Underworld had the head of a lioness and the body of a woman; in her arms she carried her pet, a deadly serpent. She summoned Belisari, the lady of the desert who was her scribe, and who came carrying the clay tablets on which all of Irkalla’s decrees would be written down. Behind these two the dead gathered. There was no light in their eyes; they were dressed not in cloth but feathers, and instead of arms and hands they had the wings of birds.

Common Depictions of Ishtar

Why Ishtar had Nothing to Do With Easter

Now that the issue of Ishtar’s symbols are cleared up and we know that she had nothing to do with bunnies and eggs, let’s consider whether or not she would have had anything to do with the Greco-Roman world of the first Christians.

The first question is whether or not the Greeks and Romans adopted this goddess when they conquered the Mediterranean. The simple answer is that they most certainly did not adopt the goddess Ishtar. In fact, the Greeks had their own version of Ishtar already. She was named Persephone. Like her Mesopotamian counterpart, Persephone was the daughter of the high god, Zeus. She also descended into the underworld, where she traded her own freedom for the life of her male lover. However, she is not associated with eggs, bunnies, or fertility.

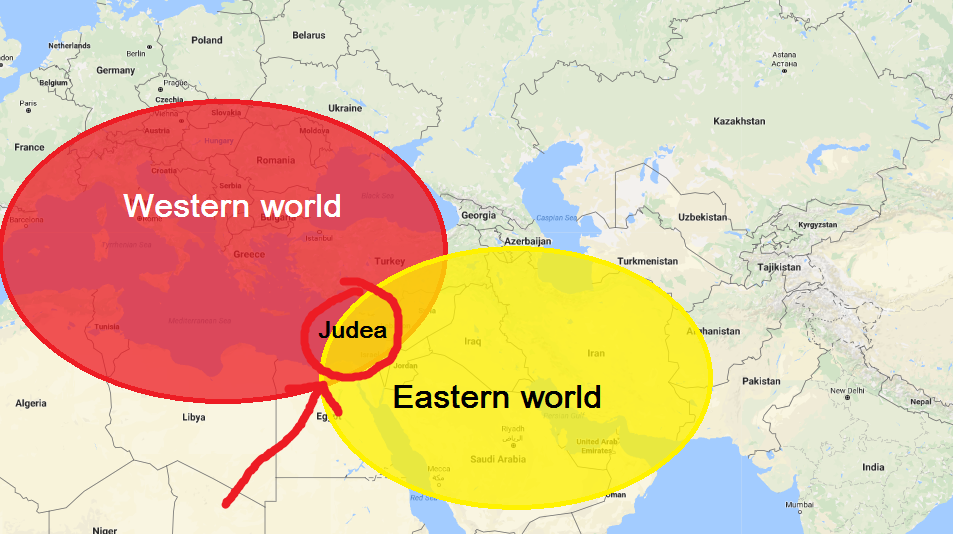

To highlight a second reason why the Greeks and eventually the Romans did not adopt Ishtar as a goddess, consider that Ishtar came from an entire different time period and region. The Roman world was a western world and the world that knew Ishtar was an eastern one.

Naturally, these drastically different regions had very different deities.

A final point of reason should be timing. The world that knew Ishtar was dead by the time of Jesus’ death.

The last major empire to recognize Ishtar was the Babylonian culture. However, they were overrun by the Persians in 539 BCE and were completely demolished. The Persian empire that took it’s place already had it’s own version of Ishtar and her name was Biducht. Either way, the Persians, who did not recognize the mainline Mesopotamian gods, fell to the Greeks in the 4th century BCE. 400 years before Christ, the Greeks erased any memory of Ishtar and her related religion.

So, what types of deities and worship was actually practiced in the Greco-Roman world that Jesus lived in?

1st Century Festivals & Deities

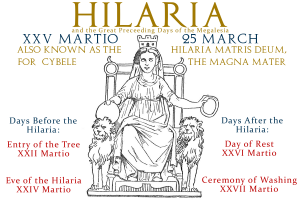

The Romans had two large spring celebrations. The first was Veneralia which was for the goddess Venus and the second was Hilaria which was for the goddess Cybele.

The Romans held Venus to be the goddess of the April festivals of new life. They called the festival Veneralia and it was on April 1st. The holiday of Hilaria was held in late March.

Both the Romans and the later Germanic cultures celebrated new life at the end of March and beginning of April (near modern day Easter). The Romans celebrated Hilaria on March 25, which they adopted from the Greeks and their festival for the goddess Cybele.

The ancient writer Herodian of Antioch (170-240 CE) explained that this celebration was often accompanied by games, masquerades, and even imitation of politicians as humor.

Some (the KJVO crowd) believe that Easter was a real Roman holiday which is why Easter was in the KJV Bible. However, not such holiday existed in the Roman world. According the legend, in Acts 12, Herod waited until after “Easter” to kill the disciple known as Peter. The theory ties in with the idea the modern day Easter was a Roman celebration that was a remnant of the Ishtar goddess worship but that theory is incorrect.

1 Now about that time Herod the king stretched forth his hands to vex certain of the church.2 And he killed James the brother of John with the sword.

3 And because he saw it pleased the Jews, he proceeded further to take Peter also. (Then were the days of unleavened bread.)

4 And when he had apprehended him, he put him in prison, and delivered him to four quaternions of soldiers to keep him; intending after Easter to bring him forth to the people. (Acts 12:1-4 KJV)

It must be recognized that there was no Roman holiday called “Easter” happening after the Passover or any other time for that matter (Passover started on the 15th and ended on the 21st. The only celebration in the Roman culture that was near the 21st was Parilia, which was a shepherd festival dedicated to cleansing the flocks. It was used in Jesus’ time also to honor the Caesar and was also accompanied by a parade of priests and noblemen. Eventually it became synonymous with the celebration of Rome’s birthday and was renamed Romaea. Naturally, this holiday withered with in the formation Roman-British empire and was completely dead during the 5th century with the rise of the Anglo-Saxon empire.

To be clear, Easter did not exist in Rome, at all, not until centuries later after Herod was dead and gone and the Catholic church claimed it from other cultures. However, the early Christians did celebrate both Passover and a crude version of what we call Easter which was just a resurrection celebration.

Pre-Easter celebrations (Christian Passover)

While the Romans were celebrating their own Roman holidays, like Veneralia, Hilaria, and Parilia, the Jews were celebrating Passover. But the early Christian church was also Jewish so the first Christians developed a Christianized form of the Passover and still called it Passover, even though it was really a celebration of Jesus’resurrection. But early Greek speaking Christians called the celebration Passover (Greek: Πάσχα). They never called it Easter until centuries later.

Additionally, the Jewish Passover (Πάσχα) feast was too close in nature and date with the Christian resurrection celebration which caused confusion for non-Jews and non-Christians because almost everyone in the first century recognized Christians as part of the Jewish religion. This issue was resolved during the reign of Constantine (306 – 337AD). Since the two holidays were often celebrated in the same week and that Constantine wanted nothing to do with the Jews, he decided to separate the Jewish Passover from the Christian Passover. This is why we don’t call Easter Passover anymore. Constantine and the Council at Nicaea ended up separating the two holidays so the Christians would be more distinct from the Jewish holiday.

Roman emperor Constantine declared: “Let us then have nothing in common with the detestable Jewish crowd; for we have received from our Saviour a different way.” (Eusebius’ Life of Constantine, Book III chapter 18)

This sentiment was made permanent by the Counsel Nicaea in 325 CE. They came to the decision that Easter will fall on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the spring equinox (from the perspective of the Northern Hemisphere), but will never fall at the beginning of the Jewish Passover.

The Actual Origin of Easter

This separate Christian celebration, distinct from Passover, is what later became known as Easter once the Roman empire decayed into the Roman-British empire (43 – 409 CE) and eventually Anglo-Saxon empire (500 – 1066 CE).

When the Roman culture declined, the Greco-Roman festival of Hilaria meshed with the Germanic festival Eostre which also accompanied tricks and jokes. The word Easter as we know it came from the Germanic celebrations that were adopted and changed by the Catholic church to be more Christian in nature. The Germanic celebration was paired with the Christian celebration of the resurrection and modern Easter was born.

Eoster was regularly pictured with eggs, bunnies, and signs of new life. Its earliest attestation is by Bede the Venerable who wrote in the 8th century CE about where the names of the months came from. This exists in two different variations based on his writings.

The heathen Anglo-Saxons called the third and fourth months “Rhedmonath” and “Esturmonath” after their goddesses Rheda and Eostra respectively. (The Reckoning of Time)

Eosturmonath has a name which is now translated “Paschal month”, and which was once called after a goddess of theirs named Eostre, in whose honour feasts were celebrated in that month. Now they designate that Paschal season by her name, calling the joys of the new rite by the time-honoured name of the old observance. (The English months)

In conclusion, Ishtar has nothing to do with modern day Easter. However, that doesn’t mean that Easter is free from pagan roots. The Germanic cultures were still very pagan and influenced the early Christian church heavily.

However, there is sadly very little archaeological information to verify the root claims that Eostre was worshiped in Europe. With the exception of the above quotes, very little factual evidence exists about this pagan goddess.

If there wasn’t a holiday called Easter during the times of the martyrdom of Peter , why is the word in the Bible and has been kept in the Bible after so many revisions from so many religious and religious research?

It’s only in some of the the early English Bibles like the KJV, Bishops, Coverdale, and the Tyndale. Other English Bible translated it correctly, such as Wycliffe, Geneva, Youngs, Darby, etc.

It’s not in a single Greek manuscript. It’s not even in the later Coptic manuscripts. It’s also not in the Latin manuscripts.

The use of Easter isn’t matter of “translation” but of how one interprets which holiday mattered to Herod. On a strictly factual basis, all of the manuscripts say Passover, not Easter.

Fantastic work. Very honest research!

oh the author is a born again Christian with a barrow to push

If you disagree with the facts then please prove the author wrong.