Sometimes a lie can be repeated so many times that even educated people believe the lie. One example is the myth that Easter came from Ishtar. Easter has nothing to do with a goddess from Mesopotamia. Another myth is that one of the popular manuscripts used in translating modern Bibles (the Sinaiticus) was discovered in the trash at a Roman Catholic monastery named after Saint Catherine. This claim is false. It’s made up. The monastery is real, though it’s not Catholic; it’s Eastern Orthodox. It’s also true that a trash bin was possibly in the story but it’s function is debated. We will clarify below.

But if it’s not true, where did it come from?

Like any believable lie, it’s got a kernel of truth.

How the Sinaiticus was found

According to Constantine Tischendorf, when he first visited the monastery, he discovered a basket full of old manuscripts & fragments. These were on parchment (leather) and he was told by a librarian (not in English) that the basket was of parchments that had been “mouldered by time” and therefore were no longer usable. Basically, a number of parchments had decayed over time, as was typical with ancient parchments. They would have to discard the unusable sections and re-create a replacement for the codex or just leave it as it was.

From Tischendorf’s account we can see that just a few damaged folios from Sinaiticus were in the basket. Those who demonetize the Sinaiticus try to make it sound like the whole codex was just discarded in the trash to be burned; this claim is false. Tischendorf visited in the mid-1800s. The codex dated at least to the 4th or 5th century. They kept the codex and preserved it already for a time period longer than any known manuscript in Greek, so there is no logical reason to conclude that they would just toss it out. Thankfully, the story is just a myth and the librarians had not tossed the codex in the trash.

However, there is more to the story that Tischendorf does not supply an answer to. In the years following Tischendorf’s visit, another man named J Rendel Harris traveled to Saint Catherine’s and spoke with the monks there. Harris being a much better speaker of the native language at Saint Catherine’s (Greek) was able to ask about Tischendorf’s visit in order to clear up some details. Harris was told by the monks that the basket that the fragments were found in was not used for the purpose of carrying fire kindling but just for the general transportation of items around the monastery. In other words, it was not a trash bin. Additionally, the monks denied throwing old manuscripts to the flames, but actually designated that particular basket as a location to place worn out parchment which would later be fixed, preserved, or replaced The misunderstanding was attributed to language or possibly that Tischendorf just wanted to be seen as a hero so the story was embellished.

It is equally possible that monk lied to save face, knowing that the fragments had value to certain groups of people. Nevertheless, whichever version of the story is the most accurate, we can conclude that 90+ % of the Sinaiticus was NOT in the waste bin and that the monks had no intention to burn the codex, at least not the salvageable portions. The codex is upwards of 900 pages, so 47 torn up parchments is hardly a reason to conclude the whole codex was being scrapped.

How the Sinaiticus was Acquired & Copied

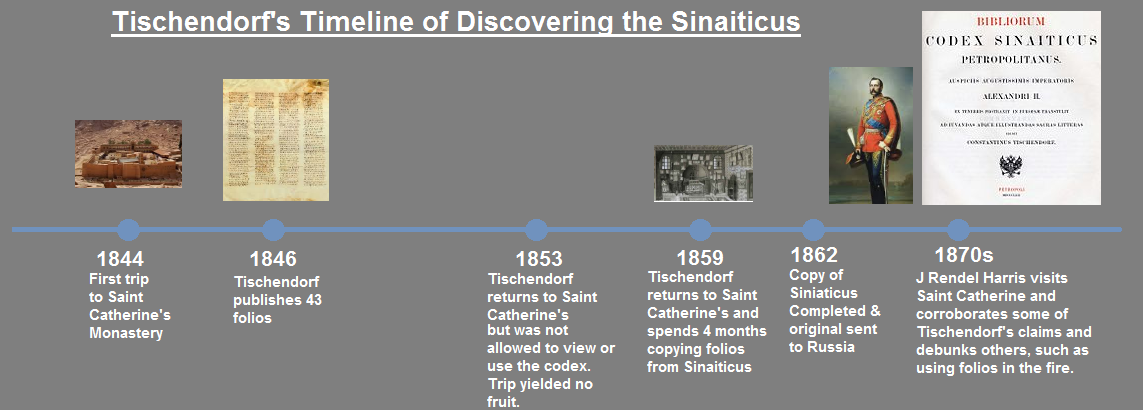

The acquiring of the codex by Tischendorf was a long and complex affair. He spent about 15 years trying to get the manuscript as well as opportunities to make copies of it. He was interested in the age of the manuscript but just as interested in the contents. Copying the contents would have fulfilled at least one of the two items he wanted. Tischendorf returned to the monastery in 1853 but was not allowed to view or copy any of the manuscripts. This was because for about 10 years the monastery was lacking a headmaster/director, and only the leader of the monastery was allowed to grant permission to use or loan the manuscripts.

His 3rd trip to the monastery was much more fruitful in 1859. This trip was under the patronage of the Russian Tsar Alexander II. It was well funded and allowed Tischendorf to spend months in Cairo copying the manuscript, a few folios at a time. This allowed the monastery to not jeopardize the whole codex but still allow Tischendorf to copy the codex. A mere 3 years later, with even more funding from Russia, Tischendorf was able to the whole codex, which he promptly copied and translated.

The manuscript given to Tischendorf for copying was well preserved and stored properly in the library of the monastery. It was not laying around in a waste bin somewhere, waiting to be burned.

Later in the 1870s, another scholar named J Rendel Harris visited the monastery and spoke with the monks who were able to corroborate some of the story but rebutted other parts, such as the claim that they were burning parts of manuscripts.

Account by Tischendorf

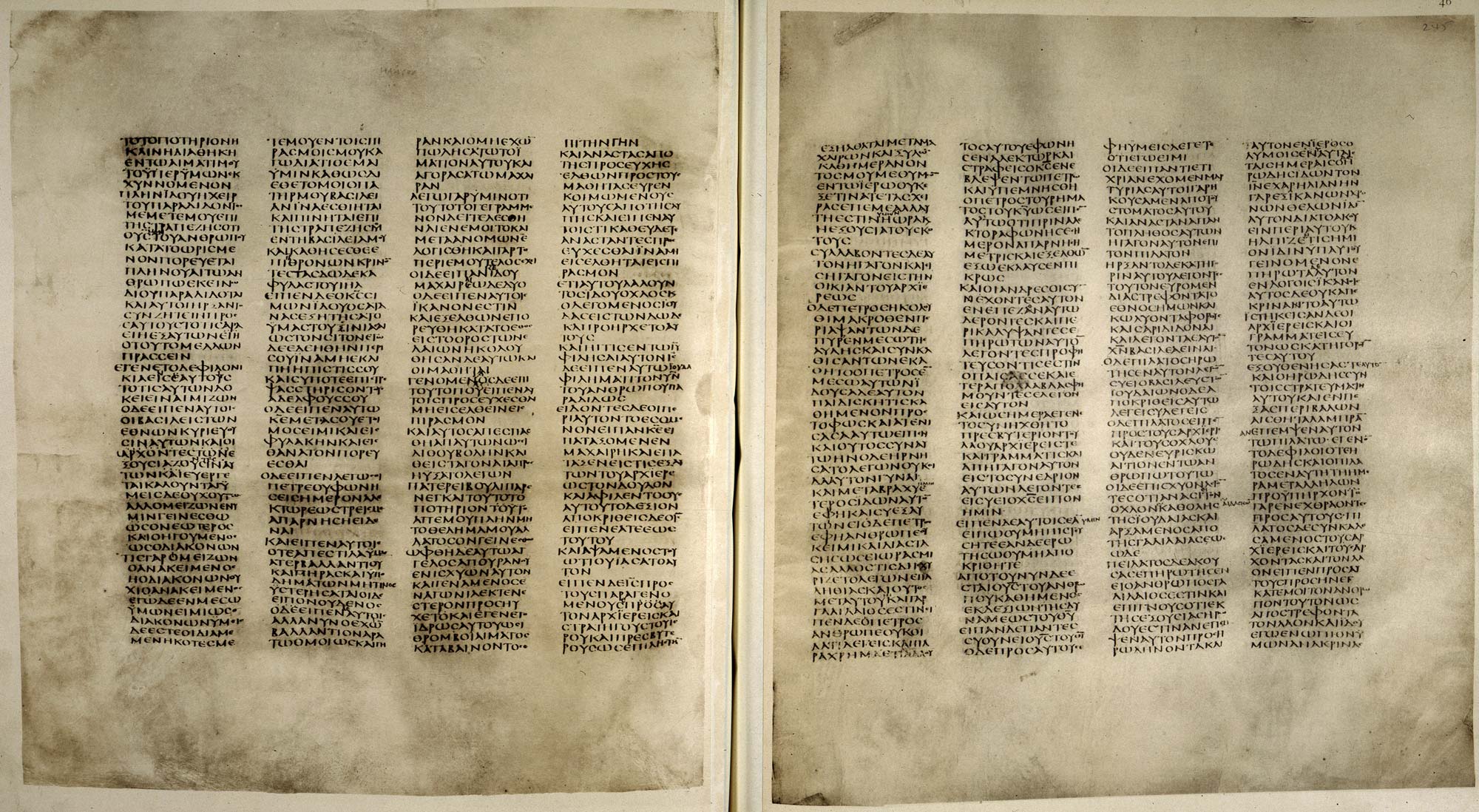

I here pass over in silence the interesting details of my travels—my audience with the pope, Gregory XVI., in May, 1843—my intercourse with Cardinal Mezzofanti, that surprising and celebrated linguist—and I come to the result of my journey to the East. It was in April, 1844, that I embarked at Leghorn for Egypt. The desire which I felt to discover some precious remains of any manuscripts, more especially Biblical, of a date 28 which would carry us back to the early times of Christianity, was realized beyond my expectations. It was at the foot of Mount Sinai, in the convent of St. Catherine, that I discovered the pearl of all my researches. In visiting the library of the monastery, in the month of May, 1844, I perceived in the middle of the great hall a large and wide basket full of old parchments; and the librarian, who was a man of information, told me that two heaps of papers like this, mouldered by time, had been already committed to the flames. What was my surprise to find amid this heap of papers a considerable number of sheets of a copy of the Old Testament in Greek, which seemed to me to be one of the most ancient that I had ever seen. The authorities of the convent allowed me to possess myself of a third of these parchments, or about forty-five sheets, all the more readily as they were destined for the fire. But I could not get them to yield up possession of the remainder. The too lively satisfaction which I had displayed, had aroused their suspicions as to the value of this manuscript. I transcribed a page of the text of Isaiah and Jeremiah, and enjoined on the monks to take religious care of all such remains which might fall in their way.

On my return to Saxony there were men of learning who at once appreciated the value of the treasure which I brought back with me. I did not divulge the name of the place where I had found it, in the hopes of returning and recovering the rest of the manuscript. I handed up to the Saxon government my rich collection of oriental manuscripts in return for the payment of all my travelling expenses. I deposited in the library of the university of Leipzig, in the shape of a collection which bears my name, fifty manuscripts, some of which are very rare and interesting. I did the same with the Sinaitic fragments, to which I gave the name of Codex Frederick Augustus, in acknowledgment of the patronage given to me by the king of Saxony; and I published them in Saxony in a sumptuous edition, in which each letter and stroke was exactly reproduced by the aid of lithography.

But these home labors upon the manuscripts which I had already safely garnered, did not allow me to forget the distant treasure which I had discovered. I made use of an influential friend, who then resided at the court of the viceroy of Egypt, to carry on negotiations for procuring the rest of the manuscript. But his attempts were, unfortunately, not successful. “The monks of the convent,” he wrote to me to say, “have, since your departure, learned the value of these sheets of parchment, and will not part with them at any price.”

I resolved, therefore, to return to the East to copy this priceless manuscript. Having set out from, Leipzig in January, 1853, I embarked at Trieste for Egypt, and in the month of February I stood, for the second time, in the convent of Sinai. This second journey was more successful even than the first, from the discoveries that I made of rare Biblical manuscripts; but I was not able to discover any further traces of the treasure of 1844. I forget: I found in a roll of papers a little fragment which, written over on both sides, contained eleven short lines of the first book of Moses, which convinced me that the manuscript originally contained the entire Old Testament, but that the greater part had been long since destroyed.

On my return I reproduced in the first volume of a collection of ancient Christian documents the page of the Sinaitic manuscript which I had transcribed in 1844, without divulging the secret of where I had found it. I confined myself to the statement that I claimed the distinction of having discovered other documents—no matter whether published in Berlin or Oxford—as I assumed that some learned travellers who had visited the convent after me had managed to carry them off.

The question now arose how to turn to use these discoveries. Not to mention a second journey which I made to Paris in 1849, I went through Germany, Switzerland, and England, devoting several years of unceasing labor to a seventh edition of my New Testament. But I felt myself more and more urged to recommence my researches in the East. Several motives, and more especially the deep reverence of all Eastern monasteries for the emperor of Russia, led me, in the autumn of 1856, to submit to the Russian government a plan of a journey for making systematic researches in the East. This proposal only aroused a jealous and fanatical opposition in St. Petersburg. People were astonished that a foreigner and a Protestant should presume to ask the support of the emperor of the Greek and orthodox church for a mission to the East. But the good cause triumphed. The interest which my proposal excited, even within the imperial circle, inclined the emperor in my favor. It obtained his approval in the month of September, 1858, and the funds which I asked for were placed at my disposal. Three months subsequently my seventh edition of the New Testament, which had cost me three years of incessant labor, appeared, and in the commencement of January, 1859, I again set sail for the East.

I cannot here refrain from mentioning the peculiar satisfaction I had experienced a little before this. A learned Englishman, one of my friends, had been sent into the East by his government to discover and purchase old Greek manuscripts, and spared no cost in obtaining them. I had cause to fear, especially for my pearl of the convent of St. Catherine; but I heard that he had not succeeded in acquiring any thing, and had not even gone as far as Sinai; “for,” as he said in his official report, “after the visit of such an antiquarian and critic as Dr. Tischendorf, I could not expect any success.” I saw by this how well advised I had been to reveal to no one my secret of 1844.

By the end of the month of January I had reached the convent of Mount Sinai. The mission with which I was intrusted entitled me to expect every consideration and attention. The prior, on saluting me, expressed a wish that I might succeed in discovering fresh supports for the truth. His kind expression of good will was verified even beyond his expectations.

After having devoted a few days in turning over the manuscripts of the convent, not without alighting here and there on some precious parchment or other, I told my Bedouins, on the 4th of February, to hold themselves in readiness to set out with their dromedaries for Cairo on the 7th, when an entirely unexpected circumstance carried me at once to the goal of all my desires. On the afternoon of this day, I was taking a walk with the steward of the convent in the neighborhood, and as we returned towards sunset, he begged me to take some refreshment with him in his cell. Scarcely had he entered the room when, resuming our former subject of conversation, he said, “And I too have read a Septuagint, i. e., a copy of the Greek translation made by the Seventy;” and so saying, he took down from the corner of the room a bulky kind of volume wrapped up in a red cloth, and laid it before me. I unrolled the cover, and discovered, to my great surprise, not only those very fragments which, fifteen years before, I had taken out of the basket, but also other parts of the Old Testament, the New Testament complete, and in addition, the Epistle of Barnabas and a part of the Pastor of Hermas. Full of joy, which this time I had the self-command to conceal from the steward and the rest of the community, I asked, as if in a careless way, for permission to take the manuscript into my sleeping-chamber, to look over it more at leisure. There by myself, I could give way to the transport of joy which I felt. I knew that I held in my hand the most precious Biblical treasure in existence—a document whose age and importance exceeded that of all the manuscripts which I had ever examined during twenty years’ study of the subject. I cannot now, I confess, recall all the emotions which I felt in that exciting moment, with such a diamond in my possession. Though my lamp was dim and the night cold, I sat down at once to transcribe the Epistle of Barnabas. For two centuries search has been made in vain for the original Greek of the first part of this epistle, which has been only known through a very faulty Latin translation. And yet this letter, from the end of the second down to the beginning of the fourth century, had an extensive authority, since many Christians assigned to it and to the Pastor of Hermas a place side by side with the inspired writings of the New Testament. This was the very reason why these two writings were both thus bound up with the Sinaitic Bible, the transcription of which is to be referred to the first half of the fourth century, and about the time of the first Christian emperor.

Early on the 5th of February, I called upon the steward, and asked permission to take the manuscript with me to Cairo, to have it there transcribed from cover to cover; but the prior had set out only two days before also for Cairo, on his way to Constantinople, to attend at the election of a new archbishop, and one of the monks would not give his consent to my request. What was then to be done? My plans were quickly decided. On the 7th, at sunrise, I took a hasty farewell of the monks, in hopes of reaching Cairo in time to get the prior’s consent. Every mark of attention was shown me on setting out. The Russian flag was hoisted from the convent walls, while the hillsides rang with the echoes of a parting salute, and the most distinguished members of the order escorted me on my way as far as the plain. The following Sunday I reached Cairo, where I was received with the same marks of good-will. The prior, who had not yet set out, at once gave his consent to my request, and also gave instructions to a Bedouin to go and fetch the manuscript with all speed. Mounted on his camel, in nine days he went from Cairo to Sinai and back, and on the 24th of February the priceless treasure was again in my hands. The time was now come at once boldly and without delay to set to work to a task of transcribing no less than a hundred and ten thousand lines, of which a great many were difficult to read, either on account of later corrections or through the ink having faded, and that in a climate where the thermometer, during March, April, and May, is never below 77º Fahrenheit in the shade. No one can say what this cost me in fatigue and exhaustion.

The relation in which I stood to the monastery gave me the opportunity of suggesting to the monks the thought of presenting the original to the emperor of Russia, as the natural protector of the Greek orthodox faith. The proposal was favorably entertained, but an unexpected obstacle arose to prevent its being acted upon. The new archbishop, unanimously elected during Easter week, and whose right it was to give a final decision in such matters, was not yet consecrated, or his nomination even accepted by the Sublime Porte. And while they were waiting for this double solemnity, the patriarch of Jerusalem protested so vigorously against the election, that a three months’ delay must intervene before the election could be ratified and the new archbishop installed. Seeing this, I resolved to set out for Jaffa and Jerusalem.

Just at this time the grand-duke Constantine of Russia, who had taken the deepest interest in my labors, arrived at Jaffa. I accompanied him to Jerusalem. I visited the ancient libraries of the holy city, that of the monastery of Saint Saba, on the shores of the Dead sea, and then those of Beyrout, Ladikia, Smyrna, and Patmos. These fresh researches were attended with the most happy results. At the time desired I returned to Cairo; but here, instead of success, only met with a fresh disappointment. The patriarch of Jerusalem still kept up his opposition; and as he carried it to the most extreme lengths, the five representatives of the convent had to remain at Constantinople, where they sought in vain for an interview with the sultan, to press their rights. Under these circumstances, the monks of Mount Sinai, although willing to do so, were unable to carry out my suggestion.

In this embarrassing state of affairs, the archbishop and his friends entreated me to use my influence on behalf of the convent. I therefore set out at once for Constantinople, with a view of there supporting the case of the five representatives. The prince Lobanow, Russian ambassador to Turkey, received me with the greatest good-will; and as he offered me hospitality in his country-house on the shores of the Bosphorus, I was able the better to attend to the negotiations which had brought me there. But our irreconcilable enemy, the influential and obstinate patriarch of Jerusalem, still had the upper hand. The archbishop was then advised to appeal himself in person to the patriarchs, archbishops, and bishops, and this plan succeeded; for before the end of the year the right of the convent was recognized, and we gained our cause. I myself brought back the news of our success to Cairo, and with it I also brought my own special request, backed with the support of Prince Lobanow.

On the 27th of September I returned to Cairo. The monks and archbishops then warmly expressed their thanks for my zealous efforts in their cause; and the following day I received from them, under the form of a loan, the Sinaitic Bible, to carry it to St. Petersburg, and there to have it copied as accurately as possible.

I set out for Egypt early in October, and on the 19th of November I presented to their imperial majesties, in the Winter Palace at Tsarkoe-Selo, my rich collection of old Greek, Syriac, Coptic, Arabic, and other manuscripts, in the middle of which the Sinaitic Bible shone like a crown. I then took the opportunity of submitting to the emperor Alexander II. a proposal of making an edition of this Bible worthy of the work and of the emperor himself, and which should be regarded as one of the greatest undertakings in critical and Biblical study.

I did not feel free to accept the brilliant offers that were made to me to settle finally, or even for a few years, in the Russian capital. It was at Leipzig, therefore, at the end of three years, and after three journeys to St. Petersburg, that I was able to carry to completion the laborious task of producing a fac-simile copy of this codex in four folio volumes.

In the month of October, 1862, I repaired to St. Petersburg to present this edition to their majesties. The emperor, who had liberally provided for the cost, and who approved the proposal of this superb manuscript appearing on the celebration of the Millenary Jubilee of the Russian monarchy, has distributed impressions of it throughout the Christian world; which, without distinction of creed, have expressed their recognition of its value. Even the pope, in an autograph letter, has sent to the editor his congratulations and admiration. It is only a few months ago that the two most celebrated universities of England, Cambridge and Oxford, desired to show me honor by conferring on me their highest academic degree. “I would rather,” said an old man, himself of the highest distinction for learning—“I would rather have discovered this Sinaitic manuscript than the Koh-i-noor of the queen of England.”

But that which I think more highly of than all these flattering distinctions is, the conviction that Providence has given to our age, in which attacks on Christianity are so common, the Sinaitic Bible, to be to us a full and clear light as to what is the word written by God, and to assist us in defending the truth by establishing its authentic form.

Conclusion

The case against the Sinaiticus being a worthy manuscript is weak. Only a tiny portion of it’s almost 900 pages were damaged and the ones that were damaged we removed not because the manuscript was poor but because this was the general practice when folios were going to be fixed, mended, copied, or replaced. It was not uncommon for a page or folio to be copied and replaced if it became badly damaged. The codex was not a 1400 year old piece of trash just sitting around in the monastery.

Additionally, it is believed that this codex (along with Vaticanus) could possibly be part of the 50 Bibles that Constantine ordered to be created in 322 CE, which was recorded by historian Eusebius. 1

I have thought it expedient to instruct your Prudence to order fifty copies of the sacred Scriptures, the provision and use of which you know to be most needful for the instruction of the Church, to be written on prepared parchment in a legible manner, and in a convenient, portable form, by professional transcribers thoroughly practised in their art.

The notion that it’s one of Constantine’s Bibles is difficult to prove, however, based on the use of Unical Majuscule script and other dating factors, scholars can deduce it’s age as authentically part of the 4th century. Majuscule script was phased out in the 5th and 6th century and replaced with Minuscule script. Also the amount of later alterations made to it demonstrate it’s of very early age, as a number of them only appear in late manuscripts

- Vita Constantini, IV,36